| |

|

|

The principle of the Inquisition was

murderous ... The popes were not only murderers in the

great style, but they also made murder a legal basis

of the Christian Church and a condition for salvation.

|

|

Lord Acton (1834-1902)

|

The term Inquisition is somewhat misleading in that over the

centuries there have been a number of inquisitions. They have

been directed against all of the groups we have looked at —

Pagans and supposed

Witches, dissenting

sects, Cathars,

Jews, Heretics,

Philosophers,

Freethinkers, Blasphemers,

Apostates,

Humanists,

Pantheists,

Unitarians,

Deists and

Atheists

as well as Muslims, Hindus and members of other religions.

In 1184 Pope Lucius III and the Emperor Frederick formulated

a programme for the repression of heretics. This document, Ad

abolendum, is sometimes known as the charter of the Inquisition,

because it set the tone for future developments. The Fourth

Lateran Council in 1215 ordered all bishops to hold an annual

inquisition, if there was a suspicion of heresy in their See.

But these Episcopal inquisitions were found to be inadequate

for the task.

The Medieval Inquisition

A roving papal Inquisition was set up in 1231 by Pope Gregory

IX. He extended existing legislation against heretics and introduced

the death penalty for them — indeed for anyone who dissented

from his views. Initially intended to be temporary, this Inquisition

was used to extirpate surviving Cathars in the Languedoc. Anyone

accused or "defamed" was treated as guilty, and no

one once defamed got off without some punishment. After 1227

inquisitorial commissions were granted only to the friars, usually

to the Dominicans. The Inquisition was now the "Dominican

Inquisition". Dominic Guzmán's threats of slavery

and death for the citizens of the Languedoc were fulfilled for

a second time. First the massacres, now the Inquisition. The

Bishop of Toulouse marked the canonisation of St Dominic on

his first Saint's Day (4 th August 1234) by burning a woman

for her Cathar beliefs. She had confessed to him as she lay

sick in bed with a fever. She was carried to a field, still

on her sickbed, and consigned to the flames, without any trial.

The churchmen then repaired for their celebratory mbanquet,

at which they thanked Saint Dominic for his miraculous assistance.1.

|

A hand crusher, fitted with a Christian

cross

to emphasise that the torture is being carried out on

behalf of the Christian God.

|

|

|

| All of the legal apparatus of the Inquisition

was developed during this period. Elsewhere, courts followed

at least the basic rules of justice: the accused knew their

accusers, they were allowed legal representation, in some

places judgement was delivered by a jury composed of peers

of the accused. The old bishops" inquisitions had been

public hearings, but these papal inquisitions were different:

now secret hearings took place before clerical judges and

prosecutors. Guilt was assumed from the start. There were

no juries, and no legal representation for the accused.

There was no habeas corpus; no disclosure of any

evidence against the accused, and no appeal. Inquisitors

were allowed to excuse each other for breaches of the rules

— which meant that in effect there were no rules*.

There were secret depositions and anonymous accusations,

torture and unlimited detention in appalling conditions

for those who failed to confess. Dead people were tried

along with the living. When found guilty their children

were disinherited. At least half the estate generally went

to the Church — so that the Church had a direct material

interest in a guilty verdict. Children and grandchildren

of those found guilty were all debarred from any secular

office.

Gregory IX's immediate successor died before assuming

the reins of office, but the next pope, Innocent IV, made

the Inquisition into a permanent institution. In

1252 he issued a bull Ad extirpanda, which explicitly

authorised the use of torture, seizure of goods and execution,

all on minimal evidence. Torture was to be administered

by the secular authority, but when this proved impractical

the inquisitors were allowed to administer it themselves

(and to absolve each other for doing so). Thereafter it

was an exceptional man, woman or child who could not quickly

be convinced of his or her heresy.

|

|

|

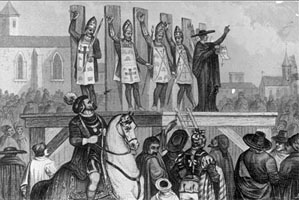

Saint Dominic Presiding over an

Auto de fe

detail, (1475) by Pedro Berruguete

For centuries Saint Dominic was hailed by Dominicans

as the Father of the Inquisition.

They commissioned this painting in his honour, showing

him presiding over an Auto de fe.

The painting reflects practices of the fifteenth

century (not the thirteenth century when Dominic

lived).

Dominicans have recently made efforts to distance

Dominic from the Inquisition.

|

|

|

|

A "Spanish Gaiter" - for crushing

victims' legs. Here a piece of wood is standing in for

a leg.

|

|

|

In theory torture could be applied only once, and could not

be such as to draw blood, to cause permanent mutilation or to

kill. Boys under the age of 14 and girls under 12 were excused.

In practice there was no one to enforce any of these safeguards,

and they were all ignored. The accused were imprisoned, often

for many months, before being examined. They were often kept

in solitary confinement, in unsanitary conditions, in a dark

dungeon, and without adequate heating, food or water. This was

deliberate, and designed to ensure that most of the accused

would already have broken by the time of the first examination.

Only the strongest characters were able to face a tribunal of

hooded figures who claimed to have heard witnesses and seen

incriminating evidence. Most were prepared to admit anything,

even though they did not know what the accusations were. Those

who failed to admit their crimes were taken to the torture chamber

and shown the instruments of torture. This too was designed

to terrify and break them — the dark chamber, the horrifying

instruments, the torturer-executioner dressed and hooded in

black. If they still failed to admit their guilt they were then

subjected to torture: men, women and children alike. Some people

were tortured for years before confessing. Only the most exceptional

could resist. Every day they risked being tortured to death*.

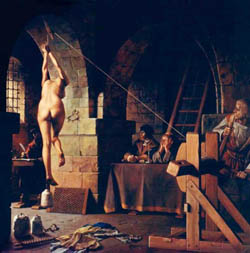

Tortures

varied from time to time and place to place, but the following

represent the more popular options. Victims were stripped and

bound. The cords were tied around the body and limbs in such

a way that they could be tightened, by a windlass if necessary,

until they acted like multiple tourniquets. By attaching the

cords to a pulley the victim could be hoisted off the ground

for hours, then dropped. Whether the victim was pulled up short

before the weight touched the floor, or allowed to fall to the

floor, the pain was acute. This was the torture of the pulley,

also known as squassation }. It was also called the

strappado, (by which name we have already encountered it being

used at Bamberg). John Howard, the prison reformer, found this

still in use in Rome in the second half of the eighteenth century*. Tortures

varied from time to time and place to place, but the following

represent the more popular options. Victims were stripped and

bound. The cords were tied around the body and limbs in such

a way that they could be tightened, by a windlass if necessary,

until they acted like multiple tourniquets. By attaching the

cords to a pulley the victim could be hoisted off the ground

for hours, then dropped. Whether the victim was pulled up short

before the weight touched the floor, or allowed to fall to the

floor, the pain was acute. This was the torture of the pulley,

also known as squassation }. It was also called the

strappado, (by which name we have already encountered it being

used at Bamberg). John Howard, the prison reformer, found this

still in use in Rome in the second half of the eighteenth century*.

The

rack was a favourite for dislocating limbs. Again, the victim

could be flogged, bathed in scalding water with lime, and have

their eyes removed with purpose designed eye-gougers. Fingernails

were pulled out. Grésillons (thumbscrews) were applied

to thumbs and big toes until the bones were crushed. The victim

was forced to sit on a spiked iron chair that could be heated

by a fire underneath until it glowed red-hot. Branding irons

and red-hot pincers were also used. The victim's feet could

be placed in a wooden frame called a boot. Wedges were then

hammered in until the bones shattered, and the "blood and

marrow spouted forth in great abundance". Alternatively

the feet could be held over an open fire, and literally roasted

until the bones fell out; or they could be placed in huge leather

boots into which boiling water was poured, or in metal boots

into which molten lead was poured. Since the holy proceedings

were conducted for the greater glory of God the instruments

of torture were sprinkled with holy water. The

rack was a favourite for dislocating limbs. Again, the victim

could be flogged, bathed in scalding water with lime, and have

their eyes removed with purpose designed eye-gougers. Fingernails

were pulled out. Grésillons (thumbscrews) were applied

to thumbs and big toes until the bones were crushed. The victim

was forced to sit on a spiked iron chair that could be heated

by a fire underneath until it glowed red-hot. Branding irons

and red-hot pincers were also used. The victim's feet could

be placed in a wooden frame called a boot. Wedges were then

hammered in until the bones shattered, and the "blood and

marrow spouted forth in great abundance". Alternatively

the feet could be held over an open fire, and literally roasted

until the bones fell out; or they could be placed in huge leather

boots into which boiling water was poured, or in metal boots

into which molten lead was poured. Since the holy proceedings

were conducted for the greater glory of God the instruments

of torture were sprinkled with holy water.

Whole

families were accused. Family members would often be induced

to incriminate each other in order to minimise the suffering

of their loved ones. Minor heretics who confessed might escape

with light sentences, whereas denial invited trouble. The inquisitor

Conrad of Marburg (or Konrad von Marburg) burned every victim

who claimed to be innocent. Whole

families were accused. Family members would often be induced

to incriminate each other in order to minimise the suffering

of their loved ones. Minor heretics who confessed might escape

with light sentences, whereas denial invited trouble. The inquisitor

Conrad of Marburg (or Konrad von Marburg) burned every victim

who claimed to be innocent.

Hearings of the Inquisition denied every aspect of natural

justice, and became ever more prejudiced as time went on. They

were held in secret, generally conducted by men whose identities

were concealed. In the Papal States and elsewhere, Dominicans

acted as both judges and prosecutors. By papal command they

were forbidden to show mercy. There was no appeal. The evidence

of embittered husbands and wives, children, servants and persons

heretical, excommunicated, perjured and criminal could be used,

secretly and without their having to face the accused, their

charges being communicated to the victim only in summary form.

No

genuine defence could be sustained. For example, if a husband

provided an alibi, saying that his wife had been asleep in his

arms when she was alleged to have been attending a witches"

sabbat, it would be explained to him that a demon had adopted

the form of his wife while she was away. The husband had been

duped. There was no way for him to prove otherwise. Spies were

employed with the incentive of payment by results. Perjury was

pardoned if it was the outcome of "zeal for the faith"

— i.e. supporting the prosecution. Loyalties were over-ridden

so that obedience to a superior was forbidden if it hindered

the inquiry, and those who helped the inquisitors were granted

the same indulgences as pilgrims to the Holy Land. Any advocates

acting for and any witnesses giving evidence on behalf of a

suspect laid themselves open to charges of abetting heresy.

No one was ever acquitted, a released person always being liable

to re-arrest and a condemned person liable to a revised sentence

with no retrial, at the discretion of the inquisitor. In theory

torture could be inflicted only once, but in practice it was

repeated as often as necessary on the pretext that it was a

single occurrence, with intervals between the sessions. Confessions

were virtually guaranteed unless the victim died under torture.

Then came the sentence, and execution of the sentence: No

genuine defence could be sustained. For example, if a husband

provided an alibi, saying that his wife had been asleep in his

arms when she was alleged to have been attending a witches"

sabbat, it would be explained to him that a demon had adopted

the form of his wife while she was away. The husband had been

duped. There was no way for him to prove otherwise. Spies were

employed with the incentive of payment by results. Perjury was

pardoned if it was the outcome of "zeal for the faith"

— i.e. supporting the prosecution. Loyalties were over-ridden

so that obedience to a superior was forbidden if it hindered

the inquiry, and those who helped the inquisitors were granted

the same indulgences as pilgrims to the Holy Land. Any advocates

acting for and any witnesses giving evidence on behalf of a

suspect laid themselves open to charges of abetting heresy.

No one was ever acquitted, a released person always being liable

to re-arrest and a condemned person liable to a revised sentence

with no retrial, at the discretion of the inquisitor. In theory

torture could be inflicted only once, but in practice it was

repeated as often as necessary on the pretext that it was a

single occurrence, with intervals between the sessions. Confessions

were virtually guaranteed unless the victim died under torture.

Then came the sentence, and execution of the sentence:

...The obdurate and relapsed were taken outside the church

and handed to the magistrates with a recommendation to mercy

and instruction that no blood be shed. The supreme hypocrisy

of this was that if the magistrate did not burn the victims

on the following day, he was himself liable to be charged

with abetting heresy*.

Almost

everyone fell within their jurisdiction. People were executed

for failing to fast during Lent, for homosexuality, fornication,

explaining scientific discoveries, and even for professional

acting. Almost

everyone fell within their jurisdiction. People were executed

for failing to fast during Lent, for homosexuality, fornication,

explaining scientific discoveries, and even for professional

acting.

In order that no blood be shed, the favoured methods of execution

did not involve the cutting of flesh. So it was that burning

and roasting were popular, the stake having been inherited from

Roman law. Estates of those found guilty were forfeit, after

the deduction of expenses. Expenses included the costs of the

investigation, torture, trial, imprisonment and execution. The

accused bore it all, including wine for the guards, meals for

the judges, and travel expenses for the torturer. Victims were

even charged for the ropes to bind them and the tar and wood

to burn them. Generally, after paying these expenses, half of

the balance of the estate went to the inquisitors and half to

the Pope, or a temporal lord. This proved such an efficient

way of raising money that it became popular to try the dead

as well as the living. Bones were dug up and burned, even after

many years in the grave. As in trials of the living, there were

no acquittals, and the heretic's property was forfeit. In practice

this meant that the heirs of the deceased were dispossessed

of their inheritances.

The Knights Templar

|

Knights Templars being burned alive

Illustration, anonymous Chronicle, From the Creation

of the World until 1384.

Bibliothèque Municipale, Besançon, France.

|

|

|

The trial of the Knights Templar demonstrates how unjust the

Inquisition could be. The charges of heresy against them were

almost certainly fabricated. No real evidence was ever produced

to support the accusations. The best that could be managed was

hearsay evidence such as that of a priest (William de la Forde)

who had heard from another priest (Patrick de Ripon) that a

Templar had once told him, under the inviolable seal of confession,

about some rather improbable goings on*.

Inquisitors obtained the most damning evidence through the use

of torture. In countries where torture was not permitted, the

Templars denied the charges, however badly they were otherwise

treated and however long they were imprisoned. As soon as torture

was applied the required confessions materialised*.

Inquisitors refused to attach their seals to depositions unless

they included confessions*,

so that only one side of the case appeared in official records.

In France, where torture was applied freely, there were many

confessions, and also many deaths under torture. Accused templars

who retracted their confessions faced death at the stake as

relapsed heretics.

Wherever the charges were investigated without applying torture,

no confessions were made and no other evidence found. When no

English Templars could be induced to confess, the

Pope insisted that torture be applied When the Archbishop

of Mainz delivered a verdict favourable to the Templars at a

provincial council, the Pope simply annulled it*.

When it looked as though the Templars in Cyprus might be acquitted,

the Pope ordered a new trial backed by torture*.

When the fate of the Templars was considered at the Council

of Vienne late in 1311 the cardinals had "a long dispute"

as to whether a defence should be heard at all*.

In the event no defence was heard and the Pope enforced the

King of France's demand that the Order be suppressed.

|

In 1310, 54 templars were burned outside

Paris.

Manuscript Image from J. Riley-Smith (ed.), The Oxford

Illustrated History of The Crusades

(Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2001), p.244

|

|

|

Under

torture, the Templar Grand Master himself, Jacques de Molay,

confessed — though it is likely that his confession was

fabricated or at least added to, since he was dumbfounded when

it was read out to him. When he tried to mount a defence on

behalf of the Templar Order, he was told that "in cases

of heresy and the faith it was necessary to proceed simply,

summarily, and without the noise of advocates and the form of

judges"*. Since all

of the Order's assets had been seized there was in any case

no way for him to mount an effective defence. By asking to do

so he invited death at the stake, as a number of churchmen pointed

out at the time. Under

torture, the Templar Grand Master himself, Jacques de Molay,

confessed — though it is likely that his confession was

fabricated or at least added to, since he was dumbfounded when

it was read out to him. When he tried to mount a defence on

behalf of the Templar Order, he was told that "in cases

of heresy and the faith it was necessary to proceed simply,

summarily, and without the noise of advocates and the form of

judges"*. Since all

of the Order's assets had been seized there was in any case

no way for him to mount an effective defence. By asking to do

so he invited death at the stake, as a number of churchmen pointed

out at the time.

After years in prison and unknown amounts of torture he confessed

in exchange for the promise of a sentence of perpetual imprisonment.

The sentence was to be delivered in public, but did not go as

planned. As an expert on the Inquisition, put it:

"The

cardinals dallied with their duty until 18 March 1314, when,

on a scaffold in front of Notre Dame, Jacques de Molay, Templar

Grand Master, Geoffroi de Charney, Master of Normandy, Hugues

de Peraud, Visitor of France, and Godefroi de Gonneville,

Master of Aquitaine, were brought forth from the jail in which

for nearly seven years they had lain, to receive the sentence

agreed upon by the cardinals, in conjunction with the Archbishop

of Sens and some other prelates whom they had called in. Considering

the offences which the culprits had confessed and confirmed,

the penance imposed was in accordance with rule—that

of perpetual imprisonment. The affair was supposed to be concluded

when, to the dismay of the prelates and wonderment of the

assembled crowd, de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney arose. They

had been guilty, they said, not of the crimes imputed to them,

but of basely betraying their Order to save their own lives.

It was pure and holy; the charges were fictitious and the

confessions false. Hastily the cardinals delivered them to

the Prevot of Paris, and retired to deliberate on this unexpected

contingency, but they were saved all trouble. When the news

was carried to Philippe he was furious. A short consultation

with his council only was required. The canons pronounced

that a relapsed heretic was to be burned without a hearing;

the facts were notorious and no formal judgment by the papal

commission need be waited for. That same day, by sunset, a

pile was erected on a small island in the Seine, the Isle

des Juifs, near the palace garden. There de Molay and de Charney

were slowly burned to death, refusing all offers of pardon

for retraction, and bearing their torment with a composure

which won for them the reputation of martyrs among the people,

who reverently collected their ashes as relics." "The

cardinals dallied with their duty until 18 March 1314, when,

on a scaffold in front of Notre Dame, Jacques de Molay, Templar

Grand Master, Geoffroi de Charney, Master of Normandy, Hugues

de Peraud, Visitor of France, and Godefroi de Gonneville,

Master of Aquitaine, were brought forth from the jail in which

for nearly seven years they had lain, to receive the sentence

agreed upon by the cardinals, in conjunction with the Archbishop

of Sens and some other prelates whom they had called in. Considering

the offences which the culprits had confessed and confirmed,

the penance imposed was in accordance with rule—that

of perpetual imprisonment. The affair was supposed to be concluded

when, to the dismay of the prelates and wonderment of the

assembled crowd, de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney arose. They

had been guilty, they said, not of the crimes imputed to them,

but of basely betraying their Order to save their own lives.

It was pure and holy; the charges were fictitious and the

confessions false. Hastily the cardinals delivered them to

the Prevot of Paris, and retired to deliberate on this unexpected

contingency, but they were saved all trouble. When the news

was carried to Philippe he was furious. A short consultation

with his council only was required. The canons pronounced

that a relapsed heretic was to be burned without a hearing;

the facts were notorious and no formal judgment by the papal

commission need be waited for. That same day, by sunset, a

pile was erected on a small island in the Seine, the Isle

des Juifs, near the palace garden. There de Molay and de Charney

were slowly burned to death, refusing all offers of pardon

for retraction, and bearing their torment with a composure

which won for them the reputation of martyrs among the people,

who reverently collected their ashes as relics."

(Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of the

Middle Ages Vol. III, NY: Hamper & Bros, Franklin

Sq. 1888, p. 325)

Jacques de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney were roasted alive,

slowly, over a smokeless fire. (A document known as the Chinon

Parchment, discovered in September 2001 by Barbara Frale

in the Vatican Secret Archives, confirms that Pope Clement V

knew Jacques de Molay and other leaders of the Order to be innocent

as early as 1208).

Templar assets were divided up between Church and State, and

interest in the fates of individual Templars immediately subsided.

|

Detail of a miniature of the burning

of Jacques de Molay (the Grand Master of the Templars)

and Geoffroi de Charney.

From the Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, BL Royal

MS 20 C vii f. 48r

(In fact they were roasted slowly, rather than burned

like this)

|

|

|

The activities of the Medieval Inquisition were so terrible

that the memory of them has survived throughout Europe to the

present day. Some Christians acknowledge that the Inquisition

was one of the most sinister that the world has ever known,

and now attribute its work to satanic forces. On the other hand

there are many others prepared to defend its record.

The Spanish Inquisition

The

Medieval Inquisition was established in Barcelona in 1233. Five

years later its authority was extended to Castile, Leon and

Navarre. This was essentially an extension of the Inquisition

established to extirpate the remnants of Catharism. Over 200

years later another inquisition was to appear : the Spanish

Inquisition. Their Roman Catholic Majesties, Ferdinand

and Isabella, established it in 1479, with the explicit sanction

of Pope Sixtus IV, who in 1483 also confirmed the Dominican

friar Thomas de Torquemada as Grand Inquisitor for Aragon and

Castile. The Inquisition was initially directed against Jewish

and Muslim converts who were suspected of returning to their

own religion, and thus being guilty of apostasy. (Many had converted

to Christianity only under threat of death.) The

Medieval Inquisition was established in Barcelona in 1233. Five

years later its authority was extended to Castile, Leon and

Navarre. This was essentially an extension of the Inquisition

established to extirpate the remnants of Catharism. Over 200

years later another inquisition was to appear : the Spanish

Inquisition. Their Roman Catholic Majesties, Ferdinand

and Isabella, established it in 1479, with the explicit sanction

of Pope Sixtus IV, who in 1483 also confirmed the Dominican

friar Thomas de Torquemada as Grand Inquisitor for Aragon and

Castile. The Inquisition was initially directed against Jewish

and Muslim converts who were suspected of returning to their

own religion, and thus being guilty of apostasy. (Many had converted

to Christianity only under threat of death.)

The first European who regularly smoked

tobacco, Rodrigo de Jerez, a crewman on the Santa Maria

was imprisoned by the Spanish Inquisition for his "sinful

and infernal" habits, because "only Devil

could give a man the power to exhale smoke from his

mouth." He was released seven years later, after

smoking tobacco had become popular.

|

|

|

The process was much the same as that of the Medieval Inquisition,

and indeed was deliberately modelled on it. It too was manned

mainly by Dominicans. They copied the methods of arrest, trial,

punishment, staffing, and procedure, even down to the blessing

of the instruments of torture. Llorente, vicar-general to the

bishop of Calahorra and historian of the Inquisition, computed

that Torquemada and his collaborators, in the course of eighteen

years, burnt at the stake 10,220 persons, 6,860 in effigy, and

otherwise punished 97,321.

There

were a few differences from the Medieval Inquisition, for example

there were cases where people were able to mount a defence and

were acquitted. Better records were kept. Some inquisitors seem

to have been relatively enlightened and were suspicious of accusations

motivated by the self-interest of accusers. Prisons seem to

have been better than most ecclesiastical prisons — there

are cases of people committing minor heresies in order to get

themselves transferred from ecclesiastical prisons to those

of the Inquisition. On the other hand, this may say more about

ecclesiastical prisons than Inquisition prisons, for even in

the latter many died before their cases were heard. In the early

days the accused were able to appoint their own defence counsel,

but by the mid-sixteenth century this had changed. If advocates

were permitted they had to be abogados de los presos,

officials of the Inquisition, dependent upon the inquisitors

for their jobs. It is fair to assume, as their clients did,

that these court officials were aware of their employers"

expectations and of the dangers of doing their jobs too well. There

were a few differences from the Medieval Inquisition, for example

there were cases where people were able to mount a defence and

were acquitted. Better records were kept. Some inquisitors seem

to have been relatively enlightened and were suspicious of accusations

motivated by the self-interest of accusers. Prisons seem to

have been better than most ecclesiastical prisons — there

are cases of people committing minor heresies in order to get

themselves transferred from ecclesiastical prisons to those

of the Inquisition. On the other hand, this may say more about

ecclesiastical prisons than Inquisition prisons, for even in

the latter many died before their cases were heard. In the early

days the accused were able to appoint their own defence counsel,

but by the mid-sixteenth century this had changed. If advocates

were permitted they had to be abogados de los presos,

officials of the Inquisition, dependent upon the inquisitors

for their jobs. It is fair to assume, as their clients did,

that these court officials were aware of their employers"

expectations and of the dangers of doing their jobs too well.

It was widely accepted that the Inquisition existed only to

rob people, as people openly affirmed*.

Both rich and poor knew that it was the rich who were most at

risk. The fact that the Inquisition funded itself from the property

it confiscated meant that in effect it burned people on commission.

Individual inquisitors also funded themselves, acquiring great

wealth during their careers. Some inquisitors were known to

have fabricated evidence in order to extort money from their

victims, but even when discovered they received no punishment*.

Similarly their staff of helpers, called familiars,

were free to commit crimes without fear of punishment by the

secular courts*. After

1518 this was formalised. Familiars enjoyed immunity from prosecution

similar to benefit of clergy or modern diplomatic immunity.

This provided another cause of popular scandal, along with their

exemption from taxation.

|

Inquisition victims wearing their distinctive

hats and carrying penitential candles

|

|

|

The activities of the inquisitors were resented by all sections

of society, and the papacy was obliged to interfere from time

to time, although the inquisitors were powerful enough to ignore

it on many occasions. Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull on 18 th

April 1482 protesting that

in Aragon, Valencia, Mallorca and Catalonia the Inquisition

has for some time been moved not by zeal for the faith and

the salvation of souls, but by lust for wealth, and that many

true and faithful Christians, on the testimony of enemies,

rivals, slaves and other lower and even less proper persons,

have without any legitimate proof been thrust into secular

prisons, tortured and condemned as relapsed heretics, deprived

of their goods and property and handed over to the secular

arm to be executed, to the peril of souls, setting a pernicious

example, and causing disgust to many*

When someone was arrested all of his or her property was seized.

This was then sold off as required to pay for the upkeep of

the person arrested. This might go on for years until the property

was all sold off. The families of the accused were not supported,

so they also suffered hardships. In some cases the children

of rich parents starved in the streets*.

Others survived by begging. The King, Ferdinand, intervened

from time to time, and later, in 1561, provision was made to

support dependents — although the effect was to use up

the sequestered assets that much faster.

The accused were invited to confess their crimes but not told

what these crimes were. Sometimes it was difficult to guess,

as any of the following were considered serious crimes: changing

bedding on a Friday, not eating pork, dressing in certain ways,

wearing earrings, speaking in foreign languages, owning foreign

books, casual swearing, criticising a priest, or failing to

show due reverence to the Inquisition. Three methods of torture

were popular, the garrucha, the toca and the

potro. The garrucha was the strappado (see

page 378) under another name. The toca was a water

torture. A linen strip was forced down the throat of the accused

and water poured down it until the stomach was distended. The

potro was a form of rack combined with tourniquets.

Detail from The Inquisition Tribunal

(Auto de fe de la Inquisición)

by Francisco Goya, painted between 1812 and 1819.

It shows an Auto de fe, or accusation of heretics,

by the tribunal of the Spanish Inquisition, inside a

church.

|

|

|

Surviving records of these torture sessions make harrowing

reading*. As the torture

progressed the victims were soon ready to admit to anything.

They would admit to having done whatever they were accused of.

But since they did not know the specifics of the accusation

they could not admit to them item by item. More torture was

applied. They admitted to whatever their accusers had said,

but again they could not be specific because they did not know

what their accusers had said. More torture was applied. They

begged for clues. They begged for mercy. They were told to confess.

They confessed to crimes, real or invented, apparently whatever

they could think of. They asked what it was the inquisitors

wanted and offered to confess to it whatever it was — still

not good enough. More torture was applied. And so it went on,

sometimes until they went mad. Sometimes they died under tortured.

Many died in prison. Others committed suicide. Of the survivors

some were disabled for life.

The lucky ones got off with penance, whipping or banishment.

Others were condemned to slow deaths in prison or in the galleys.

As the writer George Ryley Scott noted in his book A History

of Torture:

Of all the punishments which the Inquisition inflicted in

the name of God, for sheer long-continued cruelty, nothing

ever rivalled the treatment of the galley-slaves, who were

flogged very nearly every day during the period they laboured

at the oars…It was a fate worse than death. For, as

everyone knew, it meant a life of the most terrible hardship

man could possibly endure and yet continue to live; it almost

inevitably entailed death long before the sentence was completed.

It meant, in the majority of instances, that the victim was

gradually whipped to death*.

Others were condemned to public execution, but this was rarely

a simple matter of dispatching the victim. Even those who confessed

immediately were tortured. Execution was not the sentence

— it was an additional sentence. At the end of

the trial a public ceremony was held called an Auto-da-fé

(Portuguese for Act of Faith). The victim was dressed

in a penitential tunic ( san benito) painted with a

design. Impenitents wore tunics painted with pictures of their

wearers burning in Hell with devils fanning the flames. On their

heads they wore 3-foot-long pointed pasteboard caps (corozas),

also painted. Around their necks they wore nooses, and in their

hands they carried candles. Anyone judged likely to speak out

against the Inquisition was gagged. After a procession came

a Mass and sermon, in which the Inquisition was praised and

heresy condemned. The sentences were read aloud and then carried

out. As usual the secular authorities were obliged to burn victims

on the Church's behalf on the grounds that ecclesia non

novit sanguinem — the Church does not shed blood.

Burning generally took place on Sundays or festivals in order

to attract the largest possible audience. Participation was

a meritorious act — so for example any persons who helped

collect firewood would earn a remission of their sins.

|

Auto de Fe (1683) by Francisco

Ricci Auto de Fe. The scence is the Plaza Mayor, Madrid,

30 June, 1680, during the Spanish Inquisition. Inquisition

victims are shown at different stages of the process.

Although it is difficult to see what is happening, the

painting gives a good idea of the scale and theatricality

of the event.

|

|

|

A

slow roasting was considered preferable to quick incineration.

Victims were tied high up on their stakes, partly to give the

crowds of faithful a good view, partly to prolong the agony.

Sometimes there was further torture before the fire was lit.

For example Protestants who refused to recant might have burning

sprigs of gorse thrust into their faces until they were burned

black. A

slow roasting was considered preferable to quick incineration.

Victims were tied high up on their stakes, partly to give the

crowds of faithful a good view, partly to prolong the agony.

Sometimes there was further torture before the fire was lit.

For example Protestants who refused to recant might have burning

sprigs of gorse thrust into their faces until they were burned

black.

The whole event was a popular festival for the devout, who

enjoyed the spectacle and ridiculed the victims in their death

agonies. The events were closely linked to royal spectacles.

The king was obliged by his coronation oath to attend these

mass burnings. Such burnings were even held to help celebrate

royal marriages.

|

Children and grandchildren of the condemned were prohibited

from becoming priests, judges or magistrates, lawyers,

notaries, accountants, physicians, surgeons, or even shopkeepers.

They could not become mayors or hold other public offices.

Some penalties passed from generation to generation without

limit. Under statutes of limpieza de sangre,

the descendants of heretics, like those of Jews and Moors,

suffered civil disabilities because of their "tainted

blood". San benitos worn by heretics were

hung up in local churches as an eternal badge of shame

so that no one should forget their heretical ancestors.

The Spanish Inquisition continued its work for centuries,

and exported its practices to the New World. The Portuguese

exported similar practices to their colonies, not only

to the New World but also east to countries like Goa.

The fact that few of the indigenous people of the New

World could be induced to convert should have meant that

there was little recidivism, and therefore little heresy.

In fact many hundreds of heresy trials were conducted

in South America.

|

|

|

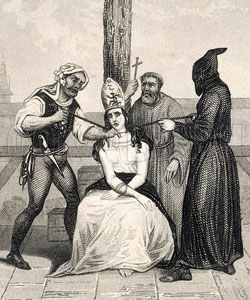

Execution of Mariana de Carabajal

at Mexico. Illustration from El Libro Rojo,

1870.

Ten members of Mariana de Carabajal's family were

tried for practicing Judaism, and burned at the

stake. Mariana (who lost her reason) was tried and

put to death at an auto-da-fé held in Mexico

City on March 25, 1601

|

|

|

|

Palace of the Inquisition - Cartagena,

Colombia

|

|

|

The Spanish Inquisition continued to execute its victims into

the nineteenth century. When the French army invaded Spain in

1808 the Dominicans in Madrid denied that they had torture chambers

in their building. The soldiers searched and found that they

did. The chambers were full of naked prisoners, many of them

insane. Similar discoveries were made throughout the country.

|

detail, Auto de fe at San Bartolome,

Otzolotepec, Mexico, by an unknown artist,

Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico

|

|

|

The Inquisition kept some records,

but we cannot know how many trials went unrecorded. Where records

were kept they were often destroyed later. Few records survive

from the victims for a number of reasons. Some were killed.

Some died in custody. Some died under torture. Some were driven

mad. Some were deprived of their tongues. Those who survived

and were still able to communicate were sworn to secrecy. So

it is that often the only evidence we have is circumstantial.

According to European folk memory the "Pear of anguish"

or "Pope's Pear" was was a favorite instrument of

the Inquisition. It was a pear shaped metal object that could

be inserted into a bodily orifice. By turning an external screw

it expanded until it tore the surrounding tissue. Pointed ends

of the 'leaves' were specifically designed to rip the throat,

intestines or cervix. It was allegedly used used on women, judged

to have 'had sex with the Devil or his familiars.' Inserted

into the vagina of the victim.

|

A Pear of Anguish, or "Pope's Pear"

- Closed

|

A Pear of Anguish, or "Pope's Pear"

- open

|

|

|

|

While it existed, the Spanish Inquisition was regarded with

horror, even by Roman Catholics from other countries who witnessed

its activities. It was abolished by Joseph Bonaparte in 1808,

but it was reintroduced by Ferdinand VII in 1814, and finally

ended by government decree on 15 th July 1834.

|

The Inquisition Tribunal or The

Inquisition Auto de fe (Auto de fe de la Inquisición)

by Francisco Goya painted between 1812 and 1819. It shows

the accusation of heretics, by the tribunal of the Spanish

Inquisition, inside a church. The accused sit in chains

wearing sanbenitos and pointed hats.. The work is now

in the collection of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes

de San Fernando in Madrid.

|

|

|

The Portuguese and Goan Inquisitions

The

Spanish Inquisition was exported not only to the Spanish colonies,

but also to Portugal and its colonies. In 1497, King Manuel

I of Portugal married, Isabella of Aragon and when she died

he married her younger sister Maria. The Spanish monarchs insisted

that a clause be included in the marriage contract requiring

the introduction of the Inquisition to Portugal, and the expulsion

or conversion of all Jews. The

Spanish Inquisition was exported not only to the Spanish colonies,

but also to Portugal and its colonies. In 1497, King Manuel

I of Portugal married, Isabella of Aragon and when she died

he married her younger sister Maria. The Spanish monarchs insisted

that a clause be included in the marriage contract requiring

the introduction of the Inquisition to Portugal, and the expulsion

or conversion of all Jews.

A large Jewish community had been well-integrated into Portuguese

society until the massacre of several hundred 'Conversos' or

'Marranos' in Lisbon in 1506, instigated by two Spanish Dominicans,

but no formal Inquisition was installed in Portugal until the

reign of the next king.

The Portuguese Inquisition (Inquisição Portuguesa)

was established in 1536 by the King of Portugal, John (João)

III. The main target of the Portuguese Inquisition were Marranos

or New Christians, those who had converted to Catholicism, both

Jews (Conversos), and Moslems (Moriscos). They

had been pressured into converting to Christianity, and were

suspected of secretly practising their old religion. Many of

the New Christians had come to Portugal to escape persecution

by the Spanish Inquisition.

As in Spain, the Inquisition was subject to the King. It was

headed by a Grand Inquisitor, selected by the king, but appointed

by the Pope. In practice the Grand Inquisitor was always a member

of the royal family. He would nominate other inquisitors. The

Portuguese Inquisition held its first auto-da-fé ("Act

of Faith") in Portugal in 1540. Courts of the Inquisition

were established in Lisbon, Coimbra, and Évora, and for

a short time in Porto, Tomar and Lamego. In Portugal's colonial

possessions, courts were established in Brazil, Cape Verde,

and Goa. The activity of the courts extended beyond New Christians

suspected of backsliding, to any form of religious non-compliance,

including cases of divination, witchcraft and even to bigamy.

The Portuguese Inquisition also censored books. Like other Inquisitions

it was renowned for its injustice, rapaciousness and cruelty.

An

auto-da-fé was the ritual of public penance of condemned

heretics and apostates that took place when the Portuguese Inquisition

had decided their punishment, followed by execution of the sentence

by the civil authorities. Auto da fé in Portuguese mean

"act of faith". The most extreme punishment imposed

was execution by burning. As the execution was more spectacular

than the penance, the term auto-da-fé came to mean the

punishment rather than the penance. An

auto-da-fé was the ritual of public penance of condemned

heretics and apostates that took place when the Portuguese Inquisition

had decided their punishment, followed by execution of the sentence

by the civil authorities. Auto da fé in Portuguese mean

"act of faith". The most extreme punishment imposed

was execution by burning. As the execution was more spectacular

than the penance, the term auto-da-fé came to mean the

punishment rather than the penance.

The auto-da-fé was a the final step in the Inquisition

process. It involved a Catholic Mass, prayer, a public procession

of those found guilty, and a public reading of their sentences.

Preparations began a month in advance and occurred only when

the inquisition authorities had enough prisoners to put on a

good show. The ritual took place in public squares or esplanades

and lasted several hours with ecclesiastical and civil authorities

in attendance. An all-night vigil would be held with prayers,

ending in Mass at daybreak and a breakfast feast. The ceremony

of public penitence then began with a procession of prisoners,

who bore elaborate symbols on their clothes. They wore a kind

of tabard called a sanbenito, made of yellow sackcloth. Designs

painted on the san benito identified the supposed crimes of

the accused. Figures of monks, dragons and demons in the act

fanning flames signified that the heretic was impenitent and

had been condemned to burn at the stake. If a victim repented

before the procession, then the sanbenito was painted with the

flames downward (fuego repolto), signifying that the victim

was not to be burnt alive, but would be strangled before being

burned. On their head victims were made to wear a tall conical

hat, also decorated to indicate the nature of their supposed

crimes. Around their neck they wore a noose. They carried a

large yellow wax candle. Prisoners' identities were kept secret

until the very last moment. They usually had no idea what their

sentence was to be, or even what the outcome of their trial

had been. Prisoners were generally taken outside the city walls

to a place called the quemadero or burning place. There the

sentences were read. Punishments included whipping and torture,

as well as burning at the stake.

|

sanbenitos worn by auto-da-fe penitents.

The man on the left wears a sanbenito that announces that

he has confessed his crime and has been given a penance

less than death. The one in the middle has confessed too

late, so will be garroted before being burned. The one

on the right will burn alive.

|

|

|

Afterwards, sanbenitos were hung up in the churches as mementos

of disgrace to their wearers and their families, and as the

trophies of the Inquisition. Sanbenitos often remained on display

for centuries, a constant embarrassment to families of those

convicted by the Inquisition.

In

the second half of the seventeenth century, António Vieira

exposed the abuses of the Portuguese Inquisition in Brazil.

His writings were condemned as rash, scandalous, erroneous,

savoring of heresy and designed to pervert the ignorant. He

was himself brought before the Inquisition. After three years

imprisonment, he was penanced in Coimbra, in 1667. Now he had

personal experience of the routine abuses and cruelty. Back

in Rome, he was free to expose the abuses. He characterized

the Holy Office of Portugal as a tribunal that served to deprive

men of their fortunes, their honor and their lives, while failing

to discriminate between guilt and innocence. He said it was

known to be holy only in name, while its works were cruelty

and injustice, unworthy of rational men, though it was always

proclaiming its superior piety. He drew up a report of two hundred

pages on the Inquisition in Portugal, with the result that after

a judicial inquiry Pope Innocent XI suspended it in Portugal

and its Empire. Autos-da-fé were stopped. Inquisitors

were instructed not to inflict sentences of relaxation (ie execution),

confiscation, or perpetual slavery in the galleys. But the Inquisition

had friends in high places. It started up again in1681, and

was soon perpetrating the same abuses as before. After the Lisbon

Earthquake of 1755 Inquisitors proposed increasing the number

of executions of heretics by way of propitiating God, an idea

which amounted to human sacrifice, as Voltaire noted at the

time. In

the second half of the seventeenth century, António Vieira

exposed the abuses of the Portuguese Inquisition in Brazil.

His writings were condemned as rash, scandalous, erroneous,

savoring of heresy and designed to pervert the ignorant. He

was himself brought before the Inquisition. After three years

imprisonment, he was penanced in Coimbra, in 1667. Now he had

personal experience of the routine abuses and cruelty. Back

in Rome, he was free to expose the abuses. He characterized

the Holy Office of Portugal as a tribunal that served to deprive

men of their fortunes, their honor and their lives, while failing

to discriminate between guilt and innocence. He said it was

known to be holy only in name, while its works were cruelty

and injustice, unworthy of rational men, though it was always

proclaiming its superior piety. He drew up a report of two hundred

pages on the Inquisition in Portugal, with the result that after

a judicial inquiry Pope Innocent XI suspended it in Portugal

and its Empire. Autos-da-fé were stopped. Inquisitors

were instructed not to inflict sentences of relaxation (ie execution),

confiscation, or perpetual slavery in the galleys. But the Inquisition

had friends in high places. It started up again in1681, and

was soon perpetrating the same abuses as before. After the Lisbon

Earthquake of 1755 Inquisitors proposed increasing the number

of executions of heretics by way of propitiating God, an idea

which amounted to human sacrifice, as Voltaire noted at the

time.

In 1773 and 1774 autos-da-fé were ended along with discrimination

on the grounds of purity of blood (Limpeza de Sangue). The Portuguese

inquisition was finally abolished in 1821 by the "General

Extraordinary and Constituent assembly of the Portuguese Nation".

Goan Inquisition

In the 15th century, the Portuguese had explored the sea route

to India and Pope Nicholas V enacted the Papal bull Romanus

pontifex. This granted the patronage of the propagation

of the Christian faith in Asia to the Portuguese and rewarded

them with a trade monopoly in newly discovered areas. Missionaries

of the Society of Jesus were sent to Portuguese colonies, where

the government provided incentives for baptised Christians.

They offered rice donations for the poor, good positions in

the Portuguese colonies for the middle class and military support

for local rulers. We know from St. Francis Xavier's own letters

that even before the Inquisition, missionaries were encouraging

the destruction of Hindu temples and religious artefacts.

In

a letter dated 1545 the Catholic missionary, St. Francis Xavier

asked King John III of Portugal for an Catholic Inquisition

to be established in Goa, in Portuguese India. The Goa Inquisition

was established in 1560 with jurisdiction over Goa and the rest

of the Portuguese empire in Asia. In

a letter dated 1545 the Catholic missionary, St. Francis Xavier

asked King John III of Portugal for an Catholic Inquisition

to be established in Goa, in Portuguese India. The Goa Inquisition

was established in 1560 with jurisdiction over Goa and the rest

of the Portuguese empire in Asia.

Some, perhaps most, Hindus and Moslems who had converted to

Christianity had done so for non-religious reasons. The starving

might accept conversion in exchange for food. Others were attracted

by social standing in Portuguese society, others by "protection"

offered by the Church. Those attracted by food were known as

"rice Christians". Orphans were indoctrinated. Others

were discriminated against if they failed to convert. The Catholic

Church was disturbed by the fact that many converts decided

on reflection to continue practising their original faith, just

as many Jewish and Moslem converts did in Spain and Portugal.

The Church considered such people apostates, Christians guilty

of the serious crime of abandoning their faith. The Inquisition

was established to punish exactly such apostate Christians.

Naturally the Goa Inquisition followed the same practices as

its parent organisation.

The inquisition was headed by a judge from Portugal. He was

answerable to (and only to) the General Counsel of the Lisbon

Inquisition. He handed downunishments in line with the Rules

that governed that Inquisition. As in the Iberian peninsula,

the Inquisition was used an instrument of social control, a

vehicle for appropriating property and a mechanism for enriching

Inquisitors. Inquisition proceedings were conducted in secret.

The

Inquisition proceeded against not only apostate converts, but

apostate descendants of converts, and indeed Christians who

retained non-Christian practices, who broke prohibitions against

the observance of Hindu or Muslim rites, or who interfered with

Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians. Sephardic Jews

living in Goa, who had fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape

the Spanish Inquisition, were also persecuted. The

Inquisition proceeded against not only apostate converts, but

apostate descendants of converts, and indeed Christians who

retained non-Christian practices, who broke prohibitions against

the observance of Hindu or Muslim rites, or who interfered with

Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians. Sephardic Jews

living in Goa, who had fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape

the Spanish Inquisition, were also persecuted.

The first inquisitors in Goa, Aleixo Dias Falcão and

Francisco Marques, established themselves in the palace previously

occupied by Goa's Sultan, obliging the Portuguese viceroy to

relocate to a more humble residence. The inquisitor's first

act was to forbid the open practice of the Hindu faith on pain

of death. The narrative of Da Fonseca describes the violence

and brutality of the inquisition. He records the need for hundreds

of prison cells to accommodate the accused.

Autos De fé started almost immediately, for second and

steadfast apostates and heretics. Again, as in Spain and Portugal,

the Inquisition burnt living people at the stake where it could,

and in effigy if it could not. We do not know how many people

were burned alive, because (as elsewhere) Inquisition records

have been lost. Those convicted of lesser crimes were forced

to work in galleys and gunpowder factories.

The Portuguese colonial administration enacted anti-Hindu laws

designed to encourage conversions to Christianity. The public

worship of Hindu gods was made unlawful. Hindus were forced

to assemble in churches to listen to Christian preaching and

supposed refutations of their satanic religion. Laws banned

Christians from keeping Hindus in their employ.

Christian agricultural labourers were forbidden from working

on land owned by Hindus and Hindus forbidden to employ Christian

labourers. Christian palanquin-bearers were forbidden from carrying

Hindus as passengers. Hindus were not allowed to enter the capital

city on horseback or palanquins. Successive violations resulted

in imprisonment.

Portuguese regulation had been oppressive from the beginning,

but they got progressively worse. Fr. Diogo De Borba and his

advisor Vicar General, Miguel Vaz had planned the conversion

of Hindus. Under this plan, in 1566, Viceroy António

de Noronha issued an order which applied to the entire area

under Portuguese rule:

I hereby order that in any area owned by my master, the king,

nobody should construct a Hindu temple and such temples already

constructed should not be repaired without my permission.

If this order is transgressed, such temples shall be, destroyed

and the goods in them shall be used to meet expenses of holy

deeds, as punishment of such transgression.

In 1567, a campaign of destroying temples in Bardez resulted

in some 300 Hindu temples being destroyed. From 1567 on Hindu

rituals were banned including marriages and cremation. Everyone

above 15 years of age was compelled to listen to Christian preaching,

on pain of punishment. In 1583 the army was co-opted to destroy

Hindu temples. Non-Christian holy books were destroyed. Filippo

Sassetti, who visited India from 1578 to 1588 wrote

The fathers of the Church forbade the Hindus under terrible

penalties the use of their own sacred books, and prevented

them from all exercise of their religion. They destroyed their

temples, and so harassed and interfered with the people that

they abandoned the city in large numbers, refusing to remain

any longer in a place where they had no liberty, and were

liable to imprisonment, torture and death if they worshipped

after their own fashion the gods of their fathers.

In 1620, further legislation was passed to prohibit the Hindus

from performing weddings. At the urging of Franciscans, the

Portuguese viceroy forbade the use of Konkani in 1684. He decreed

that within three years, the local people should speak the Portuguese

tongue and use it in all their dealings in Portuguese territories.

The penalties for violation was be imprisonment. . The same

decree provided that all the non-Christian symbols along with

books written in local languages should be destroyed. This decree

was confirmed by the King of Portugal three years later.

|

A procession by the inquisition in Goa

- Dominicans in the lead, victims in sanbenitos behind.

From Picart's 'The Ceremonies and Religious Customs

of the Idolatrous Nations' (English version, London,

1733-38)

|

|

|

In the laws and prohibitions of the inquisition in 1736, over

42 Hindu practices were prohibited, including the wearing of

ponytails, greeting people with Namaste, wearing sandals, and

even removing one's slippers on entering a church. Many restrictions

were purely cultural, not religious. Traditional musical instruments

and singing were prohibited, and were replaced by Western music.

Hindus were renamed when they converted and were not permitted

to use their original names. Converts were expected to adopt

western diets including pork and beef, and to drink alcohol.

These measures were intended partially to prove the converts'

commitment, and partly to help isolate converts from non-Christian

friends and family members. Those who persistently refused to

give up their ancient Hindu practices were declared apostates

or heretics and condemned to death. Restrictions on the local

language were also tightened. In 1812, the Archbishop of Goa

decreed that Konkani should be restricted in schools. In 1847,

this prohibition was extended to seminaries. In 1869, Konkani

was completely banned in schools. Konkani became the lingua

de criados ("language of servants").

The

Inquisition also persecuted local Jews and Syrian Christians

in Kerala, representatives of an early Christian tradition older

than Roman Catholicism, that survives today as the Jacobite

Christianity. In 1599 the Synod of Diamper authorised the forceable

conversion of the "Syriac Saint Thomas Christians"

on the grounds that they were Nestorian heretics. Assassination

attempts were made against Syriac Church leaders. Every known

item of Syriac literature was burnt. Syriac altars were pulled

down to make way for Catholic altars. Syriac Christians later

swore the Coonan Cross Oath, severing relations with the Catholic

Church. The

Inquisition also persecuted local Jews and Syrian Christians

in Kerala, representatives of an early Christian tradition older

than Roman Catholicism, that survives today as the Jacobite

Christianity. In 1599 the Synod of Diamper authorised the forceable

conversion of the "Syriac Saint Thomas Christians"

on the grounds that they were Nestorian heretics. Assassination

attempts were made against Syriac Church leaders. Every known

item of Syriac literature was burnt. Syriac altars were pulled

down to make way for Catholic altars. Syriac Christians later

swore the Coonan Cross Oath, severing relations with the Catholic

Church.

Voltaire said of the Goa Inquisition, that "The Portuguese

monks made us believe that the people worshiped the devil, and

it is they who have served him".*.Historian

Alfredo de Mello describes the Christian orders of Goan inquisition

as nefarious, fiendish, lustful, and corrupt, a view in line

with the views of a number of European visitors to Goa between

1560 and 1812 who recorded their experience in books and letters.

Most of the Goa Inquisition's records were destroyed after

its abolition in 1812, so it is impossible to establish the

number of Hindus, Moslems, Jews, non-Catholic Christians and

others put on trial, nor the numbers burned alive or otherwise

punished. A legacy of bitterness about Catholic attrocities

continues to the present day, witnessed by a number of books

on the topic published in India.

The Konkani language received official recognition in 1987

when the Indian government recognised it as the official language

of Goa.

The Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, more correctly the Congregation

of the Inquisition, was set up in 1542 by Pope Paul III

to help eradicate Protestantism from Italy. It was composed

of cardinals, one of whom had proposed its establishment in

the first place. He later became Pope himself, taking the name

Paul IV. A keen opponent of the free exchange of ideas, he enjoys

the distinction of having put even his own writings on the Index.

Procedures

of the Roman Inquisition were no more just than those of earlier

inquisitions, and executions became more common than in Spain.

Freethinkers and scientists were added to the existing categories

of victim for torture and execution. It was this inquisition

that was responsible for burning the foremost philosopher of

the Italian Renaissance, Giordano Bruno, in 1600; and for inducing

the foremost scientist, Galileo, to recant under the threat

of torture. Procedures

of the Roman Inquisition were no more just than those of earlier

inquisitions, and executions became more common than in Spain.

Freethinkers and scientists were added to the existing categories

of victim for torture and execution. It was this inquisition

that was responsible for burning the foremost philosopher of

the Italian Renaissance, Giordano Bruno, in 1600; and for inducing

the foremost scientist, Galileo, to recant under the threat

of torture.

Book burning was as popular as elsewhere, but political repression

added a new dimension. This persecution too continued for centuries,

until the papacy became too far out of step with the rest of

Western Christendom. Eventually the Church decided to change

its ways, or at least give the appearance of changing them.

Pope Pius VII purported to forbid the use of torture in 1816,

although in practice it continued to be used for decades to

come. Public burnings became something of an embarrassment too.

The answer was not to abandon executions but to carry them out

more discreetly. Pius IX, in an edict of 1856, sanctioned "secret

execution". In the Papal States things had changed little

since the Middle Ages — it was for example still a crime

to eat meat on a feast day. Political trials were conducted

by priests, whose power was absolute. Again, the accused were

not permitted legal representation, nor were they allowed to

face their accusers. All this came to an end only in 1870, when

the Papal States were seized. The last prisoners of the Inquisition

were released , and the Pope became a self-confined prisoner

in his own palace.

In

1908 the Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Inquisition changed

its name to the Holy Office. In 1967 it changed it

again, this time to the Congregation for the Doctrine of

the Faith. It still functions from a large building near

the sacristy of St Peter's in Rome. Since 1870 its dungeons

have been converted into offices. Despite the name change, there

is no apparent embarrassment about its history. On the contrary

it still conducts heresy trials according to rules that breach

what are elsewhere regarded as elementary rules of natural justice. In

1908 the Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Inquisition changed

its name to the Holy Office. In 1967 it changed it

again, this time to the Congregation for the Doctrine of

the Faith. It still functions from a large building near

the sacristy of St Peter's in Rome. Since 1870 its dungeons

have been converted into offices. Despite the name change, there

is no apparent embarrassment about its history. On the contrary

it still conducts heresy trials according to rules that breach

what are elsewhere regarded as elementary rules of natural justice.

Despite the methodical destruction of Church torture chambers

in modern times there is still evidence of their existence —

not only medieval records but the testimony of early penal reformers

like John Howard (1726—1790 ). Other reliable witnesses

also recorded the horrors they encountered. The Victorian architect

who saved the Cité of Carcassonne found not only chains

in the bishop's prison, but human bones still attached to them*.

Museums throughout Europe display instruments of torture carefully

designed to inflict the maximum of pain over prolonged periods

without shedding blood (a Papal requirement).

Because so many records have been lost, no one knows how many

men, women and children were tortured or burned to death over

the centuries by the various inquisitions. Similarly undetermined

is the number of families dispossessed, children orphaned, communities

destroyed. All we can say with certainty is that the pain and

suffering that was caused is incalculable. Even sources sympathetic

to the Roman Church accept estimates in excess of nine million.

One irony is that the Medieval, Spanish and Roman Inquisitions

would all have burned Jesus as a persistent heretic if he had

appeared before them. They might each have done so on different

grounds: for example for advocating absolute poverty, for practising

Judaism, and for criticising St Peter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

| |

| |

| More Books |

|

|

|