| |

|

|

For I have done your bidding, I have

slain mine enemies in your name. I have put women and

children to death in your honour, I have caused great

pain among them, for your glory.

|

|

Psalms, 5:4-10

|

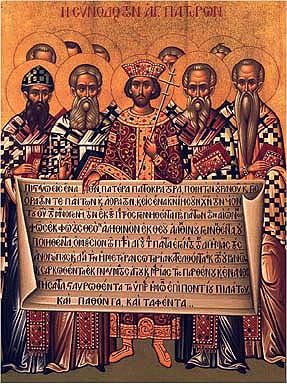

When

one of the branches of the Christian Church became the official

Church of the Roman Empire, the Emperor soon became its official

head. He occupied a position as a sort of supreme patriarch

among patriarchs, and supreme bishop among bishops. On 27 February

380, the Emperor Theodosius I formally established Nicene Christianity

as the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica.

From now on, this one form of Christianity would be the sole

permissible religion Justinian definitively established a system

of church government, now called Caesaropapism, believing "he

had the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest

details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the

theological opinions to be held in the Church". 1 When

one of the branches of the Christian Church became the official

Church of the Roman Empire, the Emperor soon became its official

head. He occupied a position as a sort of supreme patriarch

among patriarchs, and supreme bishop among bishops. On 27 February

380, the Emperor Theodosius I formally established Nicene Christianity

as the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica.

From now on, this one form of Christianity would be the sole

permissible religion Justinian definitively established a system

of church government, now called Caesaropapism, believing "he

had the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest

details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the

theological opinions to be held in the Church". 1

The Emperor exercised absolute control over the Church just

as he exercised absolute control over the state, and it was

not long before the arrangement was confirmed by declaring the

Emperor to be infallible. For many centuries it was accepted

Christian doctrine that the Emperor was the head of the Christian

Church - Pontifex Maximus and Bishop of Bishops, that senior

churchmen could be appointed by him, or at least appointed with

his approval, that he alone convoked and presided over Universal

Church Councils, that he enjoyed privileged direct communication

with God, and that he was able to declare doctrine without reference

to anyone else. Emperors such as Basiliscus, Zeno, Justinian

I, Heraclius, and Constans II convoked councils to issue the

edicts they had written, and in some cases they issued edicts

themselves without reference to Church council or anyone else.

The Emperor protected and favoured the Christian Church, and

managed its administration. He not only appointed Patriarchs,

but also set the territorial boundaries of their Patriarchies.

The system of Caesaropapism extended throughout Christendom.

At this time The Western ("Roman Catholic") Church

was still one of the Patriarchies of the Orthodox Church, and

was subject to caesaropapism just as much as the Eastern patriarchies.

Bishops of Rome often took advantage of disputes between the

East and West to try to escape from the power of the Emperor

based in Constantinople, but without success. When the Emperor

Justinian I reconquered the Italian peninsula in the Gothic

War (535-554) he reestablished traditional arrangements, and

appointed the next three bishops of Rome. This practice was

continued by his successors and was later delegated to the Exarch

of Ravenna. Once again, popes required the approval of the Byzantine

Emperor for their Episcopal consecration, and a long string

of them were appointed from the East. With the exception of

Pope Martin I, none of the 33 popes during this period questioned

the authority of the Byzantine monarch to confirm the election

of the bishop of Rome before consecration could occur2,

and it is instructive to review what happened to Martin.

Pope

Martin I was consecrated without waiting for imperial approval.

He also convoked a purported Church Council on his own authority.

As a result, he was arrested by imperial troops, taken to Constantinople,

tried and found guilty of treason, and exiled to Crimea where

he died in 655. While he still lived a replacement pope, Pope

Eugene I was appointed to replace him. Pope

Martin I was consecrated without waiting for imperial approval.

He also convoked a purported Church Council on his own authority.

As a result, he was arrested by imperial troops, taken to Constantinople,

tried and found guilty of treason, and exiled to Crimea where

he died in 655. While he still lived a replacement pope, Pope

Eugene I was appointed to replace him.

After 752, the Emperor was not able to enforce the traditional

caesaropapal system, and soon the Papacy was finding ways the

exploit the power vacuum. Instead of the Church being subject

the Emperor, it would be much better for the Western Church

to have the Empire being subject to the Bishop of Rome. This

was the occasion for the creation of a forgery known as the

Donation of Constantine. According to this eighth century forgery,

the Emperor Constantine had given the papacy supreme temporal

power, including the right to appoint Emperors. Church and State

were still one, but now the caesaropapal system was replaced

by a theocracy. All that was needed now was an unsuspecting

ruler to play the part of subordinate Emperor. Charles I, King

of the Franks and King of Italy, was duly crowned as a Holy

Roman Emperor in the year 800. Charlemagne, as he is better

known, became first emperor in western Europe since the collapse

of the Western Roman Empire three centuries earlier. A long

line of German successors were also considered to be Roman Emperors.

It is for this reason that up until 1918, the King of the Germans

was styled caesar, or in German, Kaiser.

The prerogatives of the real emperors still resident in Constantinople

in AD 800 were now claimed by the papacy. Now the Pope was Pontifex

Maximus and Bishop of Bishops. Now he was supreme head of the

Church. Now, he appointed Patriarchs and convoked Church Councils.

Now, he enjoyed direct communication with God. Now, his opinions

were infallible. Of course, the Eastern Emperor and his patriarchs

immediately saw the imposture, but they were powerless to react.

Soon, the Kings and nobles of Europe would feel the implications

too. For centuries they had regarded Church offices as their

personal possessions, to be awarded as gifts, bribes and prizes.

Normal practice had been for a ruler to appoint his second son

to the local bishopric. Soon the Church would be preventing

rulers from appointing their own nominees, and reserving this

lucrative practice to the Church. This so-called "investiture

controversy" was in fact a number of controversies spread

across Christendom, over many centuries.

|

On the left a coin of Caesar Augustus.

27 B.C. - A.D. 14: Lugdunum (Lyon) mint.

On the right a coin of Pope Leo XIII

They both bear the abreviation PONT MAX, standing for

Pontifex Maximus

- one of many examples of popes apropriating imperial

titles.

|

|

|

The first controversy arose because in practice the new Emperors

soon became more powerful than popes, and much preferred a version

of the traditional arrangement where Emperors appointed puppet

popes, rather than the new arrangement, which they correctly

suspected of being fraudulent, where popes appointed puppet

emperors. A crisis was precipitated when a group within the

church appropriated the power of investiture from the Holy Roman

Emperor and handing it to the Church. This had not been possible

as long as the emperor maintained the physical power to appoint

and depose the pope, so a first step had been to remove the

papacy from the control of the emperor. An opportunity came

in 1056 when Henry IV became German king at the age of six years.

Churchmen seized the opportunity to take the papacy by force

while Henry was still a child and unable to react. In 1059 a

church council in Rome declared, with In nomine domini,

that members of the secular nobility could have no part in the

selection of popes. They created a new electoral college, the

College of Cardinals, made up entirely of church officials.

They now had a new alternative method of creating popes.

Bolstered by forgeries and his College of Cardinals, Pope Gregory

VII was soon in a position to assert his new authority against

the now adult emperor Henry IV. In 1075 Gregory claimed in his

Dictatus papae that the deposition of an emperor lay within

the sole power of the pope. The document declared that the Roman

church was founded by God alone and that papal power was the

sole universal power. A council held in the Lateran in February

the same year decreed that the pope alone could appoint or depose

churchmen or move them from see to see.

|

Fantasy recorded as fact. The Emperor

Constantine hands his tiara (phrygium) to Sylvester, Bishop

of Rome - ceding temporal power.

This fresco of the imaginary donation is in Santi Quattro

Coronati, Rome, and dates from 1246

|

|

|

Henry IV continued to appoint his own bishops and reacted to

Dictatus papae by sending Pope Gregory VII a letter in

which he withdrew imperial support. His letter started, "Henry,

king not through usurpation but through the holy ordination

of God, to Hildebrand, at present not pope but false monk".

It called for the election of a new pope. His letter ended,

"I, Henry, king by the grace of God, with all of my Bishops,

say to you, come down, come down, and be damned throughout the

ages." The situation was exacerbated when Henry IV installed

his chaplain, Tedald, as Bishop of Milan. Gregory responded

in 1076 by excommunicating Henry and purporting to depose him

as German king. Both King and Pope ended up humiliated in the

battles that followed. At one stage,Henry was forced to beg

forgiveness (a favourite theme in Catholic art). At another,

to save his life, Gregory VII called on his Norman allies who

rescued him in 1085. While doing this, the Normans sacked Rome,

causing the citizens to rise against Gregory. The pope was forced

to flee Rome and died soon afterwards. For the moment, the problem

was resolved, but Investiture controversies would continue for

centuries. The final compromise was that neither pope nor emperor

purported to have the right to appoint the other, and both accepted

that the other did have a right of veto over elections. So it

was that for centuries reigning popes held a right of veto over

the election of new emperors, and reigning emperors held a right

of veto over the election of new popes.

|

The Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV was at

one stage reduced to begging for mercy from Pope Gregory

VII.

Here he is, along with his wife and young son, being watched

by those inside the Pope's residence,, spending three

days barefoot in the snow at Canossa before the door is

opened to him.

|

|

|

In the Languedoc, investiture controversies provided a sub-text

to the crusade against the Cathars

in the first half of the thirteenth century. Assisted by the

might of crusaders, the traditional practice of noblemen appointing

family members to bishoprics was replaced by a new practice

of papal nominations. Soon the French Kings would be challenged

in a similar way, but the immediate challenge was overcome by

the expedient of imposing a distinctively French form of caesaropapism,

where French Kings appointed a string of seven puppet Popes

and kept them under a watchful royal eye, close at hand, in

Avignon. This was the period of the so-called Babylonian Exile

of the papacy which lasted from 1309 to 1376. Once the papacy

escaped French control, the French investiture controversy continued

up until the French Revolution.

|

The Palace of the Popes, in Avignon,

now in France

|

|

The

idea of caesaropapism had a clear appeal to anyone who stood

to benefit from it, and in different forms it appeared not only

in the French Church, but also Russian and English Churches.

Back in the East, the original form of caesaropapism continued

in Constantinople, with Byzantine Emperors heading and controlling

the Orthodox Church. When Constantinople fell to the Moslem

Turks in 1453, caesaropapism did not end. By 1554 it had been

revived, later to multiply into Greek, Cypriot and Russian variations. The

idea of caesaropapism had a clear appeal to anyone who stood

to benefit from it, and in different forms it appeared not only

in the French Church, but also Russian and English Churches.

Back in the East, the original form of caesaropapism continued

in Constantinople, with Byzantine Emperors heading and controlling

the Orthodox Church. When Constantinople fell to the Moslem

Turks in 1453, caesaropapism did not end. By 1554 it had been

revived, later to multiply into Greek, Cypriot and Russian variations.

Within the Greek Orthodox Church it morphed into a strange

new form of Caesaropapism inside the Ottoman Empire with a Muslim

Emperor (the Sultan) appointing the Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople.

The Sultan was called Kayser-i-Rûm "Caesar

of Rome", while the Patriarch was the millet-bashi

(Ethnarch) of the Millet of Rûm. Under the Sultan,

the Patriarch administered a separate Orthodox legal system,

based on Justinian's code, enjoying the power to fine, imprison

and exile. This system continued until 1923, and even today

the Patriarch retains control over Mount Athos, more properly

known as the "Autonomous Monastic State of the Holy Mountain".

Another caesarolopalist system survived even longer in Cyprus.

When Michail Christodolou Mouskos became Archbishop Makarios

III of Cyprus in 1950 his role was not only the head of the

Orthodox Church in Cyprus, but also the Ethnarch, the secular

leader of the country. This dual role survived up until his

death in 1977.

After it became clear that Constantinople would never be recovered

for Christendom, the Russian Orthodox Church adapted itself

to the new reality. Moscow was declared the "Third Rome"

- the third Christian capital after Rome and Constantinople.

At the same time Russian rulers became Emperors. They referred

to themselves as Caesars, or in the Russian form, Czars.

Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible) formally assumed the title Czar

in 1547 and subordinated the Russian Orthodox Church to the

state, in imitation of the original Orthodox model. In 1721,

Peter the Great abolished the patriarchate and made the church

a department of government, copying the original model even

more closely.

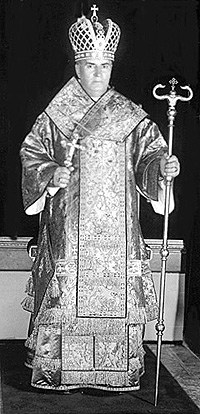

|

An Orthodox Bishop

wearing a distinctive mitre-crown

|

A Russian Czar,

also wearing a distinctive mitre-crown

|

|

|

|

In England, kings had always enjoyed jurisdiction over the

Christian Churches, both Celtic and Roman. This was made explicit

in law by the first line of Magna Carta:

In primis concessisse Deo et hac presenti carta nostra confirmasse,

pro nobis et heredibus nostris in perpetuum, quod Anglicana

ecclesie libera sit, ...

First, We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter

have confirmed, for Us and our Heirs for ever, that the Church

of England shall be free ...

The intention is ambiguous, but one fact is clear - the Church

of England was seen as the king's to dispose of as he wished

- it did not belong to pope; it did not even belong to God;

it belonged to the English Crown. For most of the time the question

of who owned the Church of England was academic as long as the

king and the pope shared common opinions. The question of caesaropapism

and investiture bubbled under the surface for many centuries,

erupting when kings appointed bishops of whom the pope did not

approve, or when popes appointed bishops of whom the king did

not approve, or when Archbishops of Canterbury fell out with

the King. The question had already exploded under King Henry

II when Henry had wanted Thomas Becket to reform the dysfunctional

application of Church Law in England. It exploded again under

King John over the appointment of Stephen Langton as Archbishop

of Canterbury (one of the factors that would lead to the creation

of Magna Carta). The question famously exploded once

again under King Henry VIII, when the question of supreme authority

over the church in England became critical. The king had no

difficulty in finding precedents to prove that he, and not the

pope, was the head of the Catholic Church in his own realm,

and that the Bishop of Rome had no authority there. Henry claimed

to enjoy direct communication with God, so as Supreme head of

the Church in England, he was able to determine Church doctrine

personally.

Of course, caesaropapism is now something of an embarrassment

to the Christian Churches, Orthodox and Catholic alike, and

to a lesser extent the Anglican Church as well. The idea that

God might give Emperors absolute jurisdiction over His Church,

and provide them with infallible doctrine is now widely regarded

as absurd. Consequently, historical examples are downplayed

by modern Churches. Most Christians are unaware that Caesaropapism

was part of standard Christian doctrine for many centuries,

nor that significant Christian doctrine was determined by lay

Emperors, some of whom had no understanding of theology and

all of whom tended to fix doctrine in accordance with their

own political interests. Neither the Orthodox nor Catholic Churches

are willing to publish a list of doctrines declared by infallible

Emperors, and much ink is dispensed by Christian apologists

in giving the impression that various forms of caesaropapism

were curious aberrations with no implications on Christian history.

Vestiges of caesaropapism have become ever more ethereal as

France, Russia, Germany, Turkey, and Cyprus successively became

republics, and the French caesar, Ottoman Kayser-i-Rûm,

Russian Csar, and German Kaiser were consigned

to history along with the Cypriot Ethnarch.

A Holy Roman Emperor tried to veto a papal election in the

early twentieth century, but now the Austro-Hungarian Empire

has gone too, along with any possibility of an emperor trying

that again. The only significant vestige today is the British

Monarch. British Kings and Queens are still Supreme Governors

of the Church of England, and they still undergo a special sort

of religious ordination and anointing during their coronation,

based on the anointing of Jewish priest-kings and early Christian

emperors. In practice the British monarch "rules"

the Church through Parliament and other organs of state. Questions

of doctrine such as the reality of hell are determined by the

Privy Council, so the Church of England is in reality a department

of state, just as the Orthodox Church was under the Christian

Emperors of Rome.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

| |

| |

| More Books |

|

|

|