| |

|

|

Orthodoxy is my doxy; heterodoxy is

another man's doxy.

|

|

Bishop William Warburton (1698-1779)

|

A famous fifth century definition of the one true Christian

faith is that which has been believed everywhere, always, and

by all1. So which is this

true faith? Does any faith satisfy the definition? Is there

a true one? And how can we tell? Is it the biggest sect, or

the one that sticks most closely to biblical teachings, or the

one that most resembles the early Church? How can we tell? Many

Churches see themselves as representing the one true faith,

standing like the trunk of a huge ancient tree, solid, straight

and ancient, while other sects have branched off, wispy and

insubstantial. They see themselves as different from all the

others. For non-Christians, a bramble bush might be a better

analogy for the Christian Church. There is not one main stem

to this bush, but a number of stems. Some of the oldest stems

have died off, and most of the vigorous growth is in the secondary

and tertiary offshoots. The bush bears the marks of some forceful

pruning over the years, yet it still lacks any main trunk and

remains a dense tangle.

Typically, what starts out as a single movement divides into

an ever-increasing number of related movements. This phenomenon

of division is generally known as schism, from the Greek word

schisma denoting a split, rent or cleft. Each schismatic

faction believes itself to hold the orthodox line. The word

orthodox is of Greek origin and means simply right

opinion. Each schismatic group is convinced that it holds

the right opinion, and is thus orthodox, representing in its

own mind the whole of the true Christian Church, other factions

having placed themselves outside it through their heterodox

beliefs. It is for this reason that many sects claimed to be

catholic (i.e. whole or comprehensive).

The word catholic is derived from the Greek word katholikos

meaning universal. The Anglican Church, the Roman Church and

the Eastern Churches all claim to be catholic.

Anglicans and many Protestants do not regard their own Churches

as dating from the Reformation. They see them as dating back

to the earliest Church, although temporarily misled by the Bishop

of Rome. As Michael Ramsey, Archbishop of Canterbury put it

: "When an Anglican is asked “where was your Church

before the Reformation?”, his best answer is to put the

counter question “Where was your face before you washed

it?” ".

From the vantage point of any one sect, all others have fallen

into error, and their adherents are thus likely to be branded

as heretics. In theory a heretical sect has broken away from

its parent Church (a fallen branch), while a schismatic sect

is still part of the tree (a split trunk). In practice the distinction

between schism and heresy is largely political. If the split

can be healed by diplomacy, then it is called a schism. But

if one side thinks it can eliminate the other by force, then

accusations of heresy tend to arise. Wherever possible the branch

is chopped off and burned.

Schisms and heresies arise in most religions. The Pharisees,

Sadducees and Samaritans mentioned in the New Testament were

heretical Jewish sects from the point of view of mainstream

Judaism. So were other groups*,

and so was Christianity when it started to diverge from its

Jewish roots. Islam is sometimes regarded as a schismatic offshoot

of both Judaism and Christianity. Soon after the death of Mohammed,

Islam split into two main groups, the Shi"ites and the

Sunni. Soon these too spawned new schismatic sub-sects. In the

remainder of this section we will review some of the schisms

within Christianity.

Jesus" followers divided into a number of opposing factions

almost immediately after his death. As we have already seen

(pages 81ff), the New Testament mentions a number of these factions,

and the Church Fathers and historians tell us of others. The

Nazarenes — followers of Jesus who continued within mainstream

Judaism — almost certainly represented the nearest approximation

to Jesus" own teachings, but this provided no guarantee

of supremacy within the wider fellowship. While the Nazarenes

continued quietly in Jerusalem, various Gnostic sects flourished

in Syria, and St Paul's faction grew fast in the Hellenic world.

All suffered further sub-schisms. The Nazarenes for example

had problems when Jesus" brother James was executed. As

the Church historian Eusebius

tells us:

After James the Just had suffered martyrdom like the Lord and

for the same reason Symeon .... was appointed bishop.... But

Thebuthis, because he was not made bishop, began secretly to

corrupt her [the Church] from the seven sects among the people

to which he himself belonged: from which came Simon (whence

the Simonians), and Cleobius (whence the Cleobians), and Dositheus

(whence the Dositheans), and Gorthaeus (whence the Goratheni),

and Masbotheus (whence the Masbothæans). Springing from

these the Menandrianists, Marcionists, Carpocratians, Valentinians,

Basilidians, and Saturnilians, every man introducing his own

opinions in his own particular way ...*

Gnostics seem never to have been a single sect, but a collection

of disparate sects, each with its own distinctive ideas, and

liable to generate new sub-schisms. Pauline Christians were

also subject to sub-schism. Already in his lifetime Paul had

cause to reprove Christians in Corinth for dividing into sects.

Quarrelling Christians there were claiming to follow different

leaders: some St Paul, some Cephas i.e. St Peter, some Apollos,

and some Christ (1 Corinthians 1:10-12). Other first century

schismatics include the Cerinthians and Nicolaitans. The Cerinthians,

like many others, held that Jesus was born of Mary and Joseph,

and that Christ descended on him at his baptism in the form

of a dove (cf. Mark 1:10-12).

Pauline Christians are now generally considered to represent

the orthodox line, but Paul had many difficulties in dealing

with others who were trying to proselytise gentiles, and who

held views other than his. On occasion Paul himself gave rise

to heterodox ideas. His statement that " ... if ye be led

of the Spirit, ye are not under the law" (Galatians 5:18)

was interpreted as meaning that the ancient laws no longer held

for Christians and there was therefore no longer any reason

for Christians to control their sexual impulses. Sexual licence

became a major problem, and Paul had to tell his followers to

stop it*. Similar ideas

were to resurface in Europe in the sixteenth century when sexual

licence again became a popular Christian theme, and the description

Antinomian was coined for those who enjoyed themselves more

than was thought proper by their Christian neighbours.

In the first and second centuries orthodoxy embraced millenarianism.

Millenarians interpreted a biblical passage (Revelation 20:2-4)

as meaning that Christ would reign for 1000 years while the

Devil was incarcerated. This view has periodically come back

into favour, generally with the assumption, based on other New

Testament passages, that the end of the world and beginning

of Christ's reign were imminent. Such ideas became popular again

in the years up to AD 1000, and yet again in the years up to

2000. Millenarianism was adopted by the Anabaptists and others

in the seventeenth century and is still taught by Mormons, Irvingites,

Adventists, the Plymouth Brethren, and many other denominations.

The Marcionites were followers of Marcion of Sinope who assembled

various writings into the earliest version of the New Testament.

Marcion, like many other early Christians, believed that Jesus

had suddenly appeared in the world as an adult. He and his followers

worshipped the god of love, adopted some Gnostic ideas, and

appointed women priests and bishops, there being no apparent

reason why they should not do so. At the time they were regarded

as more or less orthodox except that they received a little

too much guidance from the Holy Spirit for their neighbours"

tastes. Their gift of prophecy tended to subvert the authority

that priests were then establishing for themselves.

Montanists were another Gnostic sect.

They followed Montanus, a Phrygian, who believed that he had

special divine knowledge not given to the apostles. They sought,

as many sects have done since, to return to the beliefs and

practices of the primitive Church. For example, they were Quartodecimans,

meaning that they kept Easter on the 14th day of the Jewish

month of Nisan, as the entire Asian diocese had done*.

A famous Church Father, Tertullian,

became a Montanist around AD 207. Montanists were millenarians

and practised speaking in tongues,

a facility that is still claimed by Pentecostalist groups. Their

keenness on the twin joys of celibacy and martyrdom, along with

a willingness of other Christians to oblige them in respect

of the latter, ensured their disappearance in the sixth century.

Quintilians were a sub-sect of Montanists, founded by a priestess

Quintilia. They used bread and cheese at the Eucharist and also

allowed women priests and bishops. Another schismatic sect was

the Alogians, who declined to identify Christ as the Word

referred to at the beginning of the John gospel. This was apparently

a reaction to Montanists, who were keen to identify the two

as being the same, as modern theologians do.

Sabellians were followers of Sabellius,

a Libyan priest. They were Unitarians, holding that Father,

Son, and Spirit represented different states (or modes or aspects)

of a single god. In later centuries the Eastern Churches

were to accuse the Roman Church of Sabellianism and would excommunicate

popes for supporting this heresy*.

Since the time of Jesus there had been a line of followers who

believed him to have been merely human, not divine. This view

seems to have come to be regarded as heretical towards the end

of the second century*.

Yet there would still be bishops holding these views within

the mainstream Church for many years to come, especially those

whose sees fell within the patriarchy of Antioch. Eventually,

late in 268, a Bishop of Antioch, Paul of Samosata,

was removed by the secular power for holding that Jesus was

not divine. From then on, bishops had to agree to the "orthodox"

line that Jesus had been divine. Those, like Priscillian, who

deviated from the newly established orthodoxy, claiming for

example that Jesus was merely an exalted prophet, could expect

torture and death.

It was also around this time that Adoptionism first became

unacceptable. As we have already seen (page 80), the story that

Jesus was not born as the son of God, but had been adopted as

a son of God, is related in the earliest gospel (the Mark gospel).

The early Christians who preferred this account to the ones

developed later were known as Adoptionists. Adoptionism became

ever less unacceptable as the doctrine of the Incarnation was

developed. The Church Father Origen was posthumously accused

of Adoptionism. This early doctrine was never successfully suppressed.

In the eighth century at least two Spanish bishops, Elipandus

of Toledo and Felix of Urgel, were still Adoptionists. The same

Adoptionist "heresy" has resurfaced repeatedly throughout

the history of Christianity.

The third century Novatians were followers of Novatian, a Roman

presbyter. Their sole distinguishing feature was that , in obedience

to the Bible (Hebrews 6:4-6) they rejected the re-admission

of those who had lapsed into paganism.

By the fourth century one particular Christian group, calling

itself catholic, gained the ascendancy. By various means it

gained influence over the Emperor Constantine, and used its

influence to crush the opposition. Under the influence of this

group the Emperor issued an edict announcing the destruction

of other denominations:

Understand now by this present statute, Novatians, Valentinians,

Marcionites, Paulinians, you who are called Cataphrygians ...

with what a tissue of lies and vanities, with what destructive

and venomous errors, your doctrines are inextricably woven!

We give you a warning ... Let none of you presume, from this

time forward, to meet in congregations. To prevent this, we

command that you be deprived of all the houses in which you

have been accustomed to meet ... and that these should be handed

over immediately to the catholic church*.

This was how "orthodoxy" was established and maintained,

by imperial edict. Orthodoxy was whatever the Emperor said it

was, so various parties vied for the Emperor's ear, hoping to

have their views declared as orthodox. Many sects arose and

died out through little more than historical accident. The Donatist

heresy, for example, began with the election of rival bishops,

Cæcilian and Donatus, at Carthage. Imperial preference,

obtained by dubious means, having favoured Cæcilian, the

followers of Donatus went into schism, setting themselves up

as the one true Church. They were distinguished by their zeal,

their hatred of their erstwhile colleagues, and their tendency

towards further schism. They persisted for over 300 years, disappearing

only when Muslims overran that part of Africa.

Further difficulties were raised by the Arians, followers of

Arius , a priest who tried to work out exactly who Christ had

been. He held that*:

- the Father and Son are distinct beings.

- the Father had created the Son.

- the Son, though divine, is less than the Father.

- the Son existed before his appearance in the world, but

not from eternity.

Since

there was no single accepted authority to settle such matters,

the Emperor Constantine convened a council in 325 to determinethe

issue. Christians from around the known world travelled to Nicæa

(modern Iznik in Turkey). There they considered the nature of

Christ. The Arians said that he had been brought into existence

to be the incarnate Word (logos) of God. Their

opponents, led by the Archdeacon Athanasius of Alexandria, claimed

that this did not go far enough, because it represented Jesus

as being a lesser being than God. The matter was settled by

Constantine himself. Unbaptised

and only half-Christian, he was well accustomed to the idea

of men being gods. He had already had his father Constantius

deified and probably expected to be deified himself after death.

One danger with the Arian line was that it might countenance

other men claiming to be sons of God. The other line accepted

the Emperor as the prime focus on Earth of divine power. There

was only one divine son of God, and he was already safely back

in Heaven, leaving the Emperor as his personal representative

on Earth. This was obviously more appealing to the Emperor. Since

there was no single accepted authority to settle such matters,

the Emperor Constantine convened a council in 325 to determinethe

issue. Christians from around the known world travelled to Nicæa

(modern Iznik in Turkey). There they considered the nature of

Christ. The Arians said that he had been brought into existence

to be the incarnate Word (logos) of God. Their

opponents, led by the Archdeacon Athanasius of Alexandria, claimed

that this did not go far enough, because it represented Jesus

as being a lesser being than God. The matter was settled by

Constantine himself. Unbaptised

and only half-Christian, he was well accustomed to the idea

of men being gods. He had already had his father Constantius

deified and probably expected to be deified himself after death.

One danger with the Arian line was that it might countenance

other men claiming to be sons of God. The other line accepted

the Emperor as the prime focus on Earth of divine power. There

was only one divine son of God, and he was already safely back

in Heaven, leaving the Emperor as his personal representative

on Earth. This was obviously more appealing to the Emperor.

A formula was drawn up that favoured Athanasius's view, and

those present were invited to sign. For those who did sign there

was an invitation to Constantine's 20th anniversary celebrations.

Those who would not sign faced banishment. Most of those present

accepted the formula and the party invitation. Some who signed

the creed undoubtedly did so for the sake of church unity. Eusebius

of Caesarea for example was clearly embarrassed about it. Afterwards

some of the signatories reflected on what they had done and

realised its significance. Eusebius of Nicomedia, Maris of Chalcedon,

and Theognis of Nicæa wrote to Constantine to express

their regrets. Eusebius of Nicomedia summed up their position

by admitting that they had committed an impious act by subscribing

to a blasphemy out of fear of the Emperor. Ironically, Constantine

had probably not understood what the controversy had been about

anyway. Gibbon neatly sums up Constantine's views on the matter:

He [Constantine] attributes the origin of the whole controversy

to a trifling and subtle question, concerning an incomprehensible

point of the law, that was foolishly asked by the bishop [Alexander

of Alexandria] and imprudently resolved by the presbyter [Arius].

He laments that the Christian people, who had the same God,

the same religion, and the same worship, should be divided by

such inconsiderable distinctions; and he seriously recommends

to the clergy of Alexandria the example of the Greek philosophers,

who could maintain their arguments without losing their temper

and assert their freedom without violating their friendship*.

So it was that Christendom adopted as orthodoxy its doctrine

about the divinity of Christ, not through the teachings of Jesus,

not from the scriptures, but in line with the wishes of a half-pagan

self-interested Emperor. After Arius's banishment, orders were

made that Arian writings should be burned, and the death sentence

was instituted for anyone found in possession of them. Belief

in Arian views gradually declined wherever Arians were persecuted.

But the story was not yet over, for Constantine subsequently

had second thoughts. Arius was recalled from exile and restored

to Imperial favour. A series of Church Councils confirmed the

Arian line, and as St Jerome

noted the whole world now became Arian*.

As Gibbon says of Arius:

His faith was approved by the Synod of Jerusalem; and the

Emperor seemed impatient to repair his injustice by issuing

an absolute command that he should be solemnly admitted to

the Communion in the cathedral of Constantinople. On the same

day, which had been fixed for the triumph of Arius, he expired;

and the strange and horrid circumstances of his death might

excite a suspicion that the orthodox saints had contributed

more efficaciously than by their prayers to deliver the church

from the most formidable of her enemies*.

Arius, and other people that orthodox Christians disliked,

died in a particularly ghastly way, their bowels exploding shortly

after a private meeting with orthodox christian leaders. The

orthodox attributed these killings to God, an explanation that

becomes ever less convincing. Once Arius was dead there was

little chance of the decision of the Council of Nicæa

being formally overturned. Even though St Athanasius, the champion

of what is now considered orthodoxy, was condemned as a heretic

by no fewer than six separate Church Councils, even though all

the principal leaders of the orthodox faction were deposed and

exiled, and even though Constantine was baptised in the last

moments of his life by an Arian bishop, nevertheless the established

doctrine was retained, though the question was not yet closed.

In the fourth century alone forty-five Church Councils considrered

the question of whether Arius had been right or wrong. Thirteen

councils came out against him, fifteen voted in his favour,

and seventeen settled for semi-Arians positions.

When Macedonius, Bishop of Constantinople expressed ideas similar

to those of Arius, he was deposed by a council of Constantinople

in 360. His followers, Macedonians, retained their semi-Arian

beliefs for years to come. The orthodox line was that Jesus

Christ was God and from now on it would be acceptable for Christians

to pray to a deity other than God the Father. As a leading modern

theologian has put it:

The practice of praying to Christ in the Liturgy, as distinct

from praying to God through Christ, appears to have originated

among the innovating "orthodox" opponents of Arianism

in the fourth century. It slowly spread, against a good deal

of opposition, eventually to produce Christocentric piety

and theology*.

Disputes have rumbled on to the present day. For many centuries

the Arian form of Christianity flourished in Romania, Bulgaria,

Spain, Gaul and Lombardy. As a number of theologians have noted,

most Western Christians today unwittingly turn out to be Arian

when questioned about their beliefs.

Questions about the nature of the Son provided endless material

for dispute in early times. Another group, the Apollinarians,

supposedly fell into error by opposing Arius. They were followers

of Apollinaris, Bishop of Laodicea, who opposed Arianism and

denied that Jesus had a human soul. They held that the Word

(logos) fulfilled that role in Jesus" case. The

First Council of Constantinople (381) condemned their views

as heretical. Other schismatic groups included the Anthropomorphites,

who believed that God had a human form; and the Agnoetae, who

denied that God was omniscient. The Collyridians offered bread-cakes

to the Virgin Mary, worshipping her as Queen of Heaven*.

The Antidicomarianites denied Mary's continued virginity, affirming

that she had had sexual intercourse with Joseph after the birth

of Jesus }. A Donatist group known as the Circumcellions flourished

briefly, propagating violence through North Africa. But they

also had a fondness for suicidal martyrdom, and soon died out

Whichever sect enjoyed the support of the Emperor was the orthodox

or catholic faction, and it generally sought to maintain its

position by a judicious mix of persecution and politicking.

When the Emperor Julian briefly rejected Christianity as the

state religion, all sects were suddenly free to persecute each

other. Within a year of Julian's accession in 361, numerous

Christian sects were at each other's throats. There were no

fewer than five bishops in Antioch, each with a mutually hostile

following. Since then the number has never again been reduced

to one.

The question of whether or not Jesus had been a man continued

to be a major point of contention. Many disputes took place

as to whether his nature was that of a human being or a God.

Nestorius (died c.451), Bishop of Constantinople,

proposed a compromise. He suggested that Christ had two distinct

natures, one human and one divine, and that Mary was the mother

only of his human one. Mary might be Christotokos,

the mother of Christ, but not Theotokos, the mother

of God. God could not have been a baby

two or three months old, he said. God had always existed. To

Nestorius it did not make sense to say that a mother could bear

a son older than herself. Furthermore he did not like the implication

that if Mary was the mother of God then she must have been a

goddess. Cyril, Bishop of Alexandria, made an issue of the matter,

apparently to further his position in the political power struggle

between the patriarchies of Constantinople and Alexandria*.

A Church Council was convened at Ephesus in 431, by the emperors

Theodosius II and Valentinian III. The council, initially consisting

of Cyril's supporters, and under his chairmanship, acclaimed

the one person line. On the same day it condemned and

deposed Nestorius, the leader of the two person party.

When Nestorius's supporters arrived the council was reopened,

since Cyril had had no authority to open the earlier session.

The decision was now reversed, and Cyril the leader of the one

person faction was deposed and excommunicated. Later, more

of Nestorius's opponents arrived. The matter was reconsidered.

Deals were negotiated to induce various parties to agree: Pelagianism

(a doctrine concerning free will) was to be condemned as a heresy

to satisfy the Western representatives; Cyprus was to be granted

ecclesiastical independence (which it still enjoys today), and

the Bishop of Jerusalem was to be promoted to patriarch. Cyril

encouraged other representatives to agree with him, providing

carrots for their support in the form of lavish bribes, and

sticks for dissent in the form of a private army of violent

monks that terrorised the city. Cyril held a third session,

similar to the first one. But the two sides would not even meet,

let alone agree. In the end the council had to be dissolved

by the Emperor Theodosius without it ever having reached a consensus.

The Emperor arrested the leaders of both sides and put them

in prison.

A few years later Cyril succeeded in bringing the matter before

another council, at Chalcedon in 451, which was more pliant.

This council condemned Nestorius, and the inevitable schism

soon followed. The Church was once again divided, and a separate

Nestorian Church was formed. It flourished in Asia, and boasted

enough bishops to rival the ones that are now considered orthodox.

Nestorians established a patriarchy at Baghdad, and their influence

extended far to the East. At one time there was a Nestorian

Archbishop of Cambaluc (modern Peking).

Ghengis Khan was well disposed to Nestorian Christians and married

his sons to Nestorian princesses. The Nestorian Church was subsequently

reduced by Islam, and all but wiped out around 1400 by the Asian

warlord Timur. Small groups of Nestorians, now known as Assyrian

Christians, survived in

Persia and Turkey up until World War I, during which their numbers

were further reduced.

Eutyches (c.380-c.456), Archimandrite of Constantinople, held

that Jesus had only one nature — a divine nature —

after the Incarnation. Eutyches was excommunicated, later reinstated,

but then exiled for his beliefs. Nevertheless he attracted many

followers. Eventually the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon (451)

decided that Jesus had possessed two natures — one human,

one divine. To hold otherwise, as the Eutychians did, was to

commit heresy. This meant that many Christians of the time were

heretics, since many held that he had been wholly divine. Those

who subscribed to Eutyches's view came to be called Monophysites.

Alexandria was a major centre for Monophysite beliefs, and the

followers of Timothy, the Monophysite Patriarch of Alexandria,

came to be regarded as a distinct group known as Timotheans.

Alexandrian Monophysites had always retained the Jewish dietary

laws and continued to practise circumcision. They have survived

in Egypt up to the present time and constitute the Coptic Church,

headed by the Patriarch of Alexandria, who is also the nominal

head of the Ethiopian (or Abyssinian) Church. Monophysite churches

have died out in Nubia, Persia, and what is now the Yemen, but

others survive, including the Armenian and Syrian, whose common

head is styled the Patriarch of Antioch.

Another major schism was that of the Pelagians in the early

fifth century. They were followers of Pelagius,

a Welsh monk who moved to Rome around the beginning of the fifth

century. Pelagius maintained that people could take the first

steps to salvation without the assistance of divine grace. His

followers advocated free will, including the ability to accept

or reject the gospel, and denied St Augustine's doctrine of

Original Sin. The Augustinian faction employed the usual tools

of debate: personal influence, under-the-table deals, and bribery

in support of their arguments, and finally won the day by the

distribution of 80 Numidian stallions to imperial cavalry officers,

whose troops enforced Augustine's version of Christian orthodoxy.

Many modern theologians are not at all certain that Pelagius

should have lost the argument, and fewer still believe that

Augustine should have won it.

In the seventh century a schism arose over the question of

how many "wills" had been possessed by Christ, with

his one "person" and two "natures". Monotheletes,

supported by Honorius the Bishop of Rome, held that he had possessed

only one. They went into schism after the Third Council of Constantinople

in 680-681 held that he had had two. The Roman Church was obliged

to disown the views of Honorius. So did others. The Maronites

of the Lebanon were originally Monothelete Christians, but have

been in communion with the Roman Church since 1182 (when a deal

was done during the Crusades). They take their name from a Syrian

hermit, St Maron, who died in 410.

An argument sometimes advanced by more innocent believers is

that the one true Church has always called itself "orthodox"

or has always called itself "catholic", while mere

sects were named after their leaders. This of course, is not

a helpful criterion, since almost all sects claim to be both

orthodox and catholic. It is also noteworthy that the groups

now regarded as orthodox and catholic also had names, just like

the groups now regarded as schismatic or heretical. Thus the

faction from which the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches

are both descended was given a dismissive name by the other

factions. Members of this sect were called Melkites ("emperor's

men") because they allied themselves with the Emperor and

depended upon him for their survival. Again, the Eastern Churches

refer to Roman Catholics as Azymites, a reference to their "heretical"

practice of using unleavened bread at the Eucharist.

People who believe absurdities will commit atrocities.

Voltaire (1694-1778)

From the fourth century onwards there had been increasing tension

between Rome and the other patriarchies. The Church under each

of the patriarchies had always been autocephalous, i.e. self-governing

and recognising no central authority except the Emperor. This

did not entitle patriarchs to change established doctrines and

practices.

From the eighth century the Roman patriarchs (whom we now call

popes) adopted a number of innovations in Western Christendom

that might seem relatively trivial now but at the time were

not acceptable to their fellow patriarchs in the East. The Nicene

creed was changed to reflect a new understanding of the role

of the Holy Spirit, and unleavened bread was used instead of

leavened bread for the Eucharist. The popes also encouraged

fasting on Saturday and tried to enforce clerical celibacy.

Later they would discover Purgatory, a place unknown to other

patriarchs. As successive bishops of Rome became ever more wayward

in the eyes of their fellow patriarchs, the more incensed those

patriarchs became. Periodically the tension became too great,

and one or more of them would accuse a pope of heresy and excommunicate

him. He would retaliate by declaring them heretic and excommunicating

them. The reasons for their irritation were not only those already

mentioned: sometimes the Bishop of Rome was claiming new honours

for himself, sometimes he was convoking councils of his own,

sometimes he was interfering in the jurisdictions of other patriarchs,

sometimes he was using forged documents to prove a point. Generally

the quarrel would be patched up and sooner or later the mutual

excommunications would be withdrawn.

By

the eleventh century the position was no longer tenable. The

Bishop of Rome was claiming exclusive rights to the title of

Pope and pressing for primacy over the whole Church, backed

up by the forged Donation of Constantine. The Patriarch

of Constantinople had had enough, and a serious rift opened

up. Attempts at reconciliation failed and in July 1054 anathemas

(formal denunciations) were exchanged. The Great Schism between

the Eastern Churches and the Western Church is conventionally

dated from this time although, as in the previous centuries,

relations would continue periodically to warm and chill, and

reconciliation was always a possibility. Indeed, at the time

the incident was not regarded as a schism, and came to be regarded

as one by the Western Church only after 1204. (Rome needed to

justify its seizure of Constantinople in that year and did so

by retrospectively regarding the exchange of anathemas in 1054

as causing a permanent split in the Church.) The anathemas were

eventually withdrawn more than 900 years later, on 7 th December

1965. By

the eleventh century the position was no longer tenable. The

Bishop of Rome was claiming exclusive rights to the title of

Pope and pressing for primacy over the whole Church, backed

up by the forged Donation of Constantine. The Patriarch

of Constantinople had had enough, and a serious rift opened

up. Attempts at reconciliation failed and in July 1054 anathemas

(formal denunciations) were exchanged. The Great Schism between

the Eastern Churches and the Western Church is conventionally

dated from this time although, as in the previous centuries,

relations would continue periodically to warm and chill, and

reconciliation was always a possibility. Indeed, at the time

the incident was not regarded as a schism, and came to be regarded

as one by the Western Church only after 1204. (Rome needed to

justify its seizure of Constantinople in that year and did so

by retrospectively regarding the exchange of anathemas in 1054

as causing a permanent split in the Church.) The anathemas were

eventually withdrawn more than 900 years later, on 7 th December

1965.

As the power of the Eastern Churches waned, the Roman Church

was successful in picking off a number of isolated religious

communities. To this day,

it has allowed these communities to keep their local customs,

including clerical marriage, even though they are in communion

with Rome (which means that they recognise, and are recognised

by, the Roman Church).

For the majority of English people there are only two religions,

Roman Catholic, which is wrong, and the rest, which don"t

matter

Duff Cooper (1890-1954), Old Men Forget

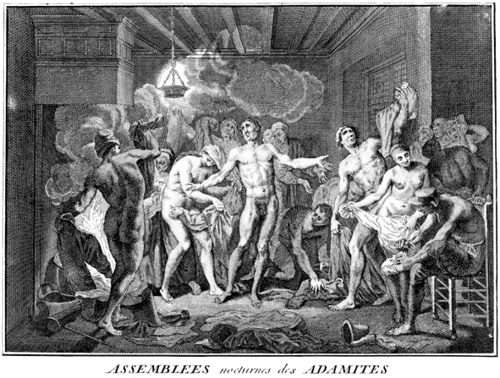

The Middle Ages saw the rise of all manner of dissident sects.

They ranged from Adamists, who insisted on conducting their

religious rites in the nude, to groups who travelled from place

to place working themselves into religious frenzy by techniques

such as dancing, chanting or flagellating each other. A major

group was that of the Adventists, who affirmed the imminence

of the Second Coming. Despite severe persecution Adventist groups

have survived into modern times. They still look forward to

the imminent Second Coming. Generally they keep to Jewish practices,

such as prohibiting the eating of pork, and keeping the Sabbath

day as required by the Ten Commandments, rather than Sunday

— hence the epithet "Seventh Day Adventists".

|

Adamists or Adamites - a seventeenth

century sect reviving antinomian ideas - also known as

Edenists

( Night Meetings of the Adamites by Francois Morellon

la Cave, 1738)

|

|

The corruption and abuses of the Roman Church in the Middle

Ages led even its own adherents to question its authority. Peter

Waldo of Lyons was originally a conventional Catholic believer

who wanted to live like the apostles. He soon attracted followers

who came to be known as Waldensians, Waldenses, or Vaudois.

He met so much opposition from his own Church that he was effectively

driven out. Soon after the movement started around 1170, Waldo

was excommunicated, after which he rejected papal authority.

Like others after him, he turned to the gospels and based his

theology on them. Waldensians were soon advocating a priesthood

of all believers and giving away their wealth. They rejected

sacraments not sanctioned by the Bible and condemned practices

such as the sale of indulgences and the adoration of saints.

Persecution followed, and continued for centuries, with unknown

thousands killed, and a few survivors taking refuge in ever

more remote places. By the late eighteenth depleted survivors

had been scattered to the alpine valleys and other remote areas.

In the nineteenth century they were assisted financially by

Protestants in the UK and USA, and many emigrated to Uruguay

and Argentina.

Other

groups split off from the Church, or were rejected from it.

The Beghards for example were essentially orthodox except that

they used vernacular translations of the Bible. Eventually they

were ejected from the Church and came to be known as Lollards.

In England John Wycliffe, a leading Oxford scholar, took the

Bible as the sole rule of faith and questioned the Roman sacraments.

His followers also came to be known as Lollards and were rejected

as unorthodox. Wycliffe's ideas spread throughout Europe and

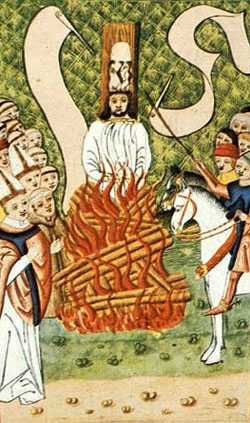

took root in Bohemia. In Prague, Jan Hus adopted them, and his

teaching attracted an ever-increasing following. In the fifteenth

century, Hussites challenged all rites, institutions and customs

not sanctioned by the Bible and questioned the Roman Church's

practice of not allowing the Communion cup to the laity. Once

again the sect was admonished and then rejected and persecuted. Other

groups split off from the Church, or were rejected from it.

The Beghards for example were essentially orthodox except that

they used vernacular translations of the Bible. Eventually they

were ejected from the Church and came to be known as Lollards.

In England John Wycliffe, a leading Oxford scholar, took the

Bible as the sole rule of faith and questioned the Roman sacraments.

His followers also came to be known as Lollards and were rejected

as unorthodox. Wycliffe's ideas spread throughout Europe and

took root in Bohemia. In Prague, Jan Hus adopted them, and his

teaching attracted an ever-increasing following. In the fifteenth

century, Hussites challenged all rites, institutions and customs

not sanctioned by the Bible and questioned the Roman Church's

practice of not allowing the Communion cup to the laity. Once

again the sect was admonished and then rejected and persecuted.

The rejection of these sects in the twelfth to fifteenth centuries

was to prepare the way for much larger schisms within the Western

Church at the Reformation. The sixteenth century saw a huge

reaction to the corruption and venality of the Roman Church.

Orthodoxy was reconsidered, and whole countries defected to

new Protestant denominations: Lutheran, Calvinist, and many

others. Martin Luther was prepared to admit into worship anything

that was not explicitly prohibited by scripture, while John

Calvin would admit only that which was expressly allowed by

it. Many German states and Scandinavian countries became Lutheran;

Holland, Scotland and Huguenot areas of France became Calvinist;

while the Anglican Church found a middle ground, purporting

to remain Catholic while adopting ever more Protestant ideas.

From around the same time, several separate groups arose that

are now known as Anabaptists.

The Roman Church has continued to generate schismatic groups

into recent times. For example, the declaration of the dogma

of papal infallibility in 1870 was unacceptable to many Roman

Catholics. Excommunicated, they formed themselves into the Old

Catholic Church, and are now in communion with the Church of

England. In 1988 Archbishop Marcel LeFebvre formally split with

the rest of the Roman Church when he ordained four new bishops.

His intention was to continue the one true Church, which he

thought had been abandoned by an excessively liberal papacy.

His followers now number hundreds of thousands in 30 countries.

Each of the new Protestant Churches started generating new

schismatic groups almost as soon as they were established. The

Anglican Church gave rise to Puritanism and later to Methodism.

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, was an Anglican priest,

who died still regarding himself as an Anglican. Animosity from

other Anglicans led to the new Methodist group becoming a separate

Church. The Methodist Church, like other schismatic groups,

behaved much like the early Christians had, and consequently

they were regarded much as the early Christians had been by

their fellow citizens. Their love feasts were believed to have

been orgies. Their fits and convulsions were advertised as the

work of God but believed by others to be evidence of demonic

possession. Their habit of luring new believers away from their

families caused massive resentment, and they were accused of

robbing widows and other vulnerable individuals of their savings,

just as the early Church had been. The new breakaway Methodist

Church soon went into schism and formed half a dozen major sub-sects,

followed by many other even smaller ones. Methodism now boasts

over 75 million members worldwide. Another schismatic group,

the Baptists, claim an estimated 47 million members in the United

States alone.

Schismatic sects with a strong Calvinist flavour include Congregationalists

and Presbyterians. Some are peculiarly attached to specific

countries. For example, the Free Church of Scotland was a schismatic

sect of the Church of Scotland, seceding from the latter in

1843. It combined with the United Presbyterian Church in 1900

to form the United Free Church of Scotland. In 1929 this joined

up again with the Church of Scotland, apart from a small minority

who retained the name of United Free Church. Tens of thousands

of schismatic sects — far too many to list here —

have arisen from the Western Church. New evangelical churches

are created virtually every day.

In the East, the Orthodox Church has also suffered a number

of schisms. Before the Great Schism of 1054, there had already

been a major schism over the use of icons. Eastern Christendom

was riven between those who worshipped icons (iconodules) and

those who rejected icons as idols and wanted to destroy them

(iconoclasts). Many people were persecuted and killed over this

issue.

Often, schisms arose over matters that seem remarkably trivial

to non-Christians. The seventeenth century saw an Eastern schism

concerning the number of fingers to be used when making the

sign of the cross. Was it two, the ancient practice used by

the Russian Orthodox Church, or three, an innovation used by

the Greek Church? Men were executed for supporting the wrong

side. The schism continues to this day, the smaller party ("The

Old Believers") having split again between the Popovtsy

(with a priesthood) and the Bezpopovtsy (without a priesthood).

There are also extensive disagreements within the Church about

the calendar. In particular the date of Easter is still problematical,

and some groups have been excommunicated for celebrating it

on one day rather than another.

Of the tens of thousands of Christian sects, virtually all

purport to be the one true mystical body of Christ and the sole

ark of salvation — the Mother Church in a monogamous relationship

with God. None has a claim to orthodoxy that, to a disinterested

observer, is noticeably superior to the others. Certainly, size

is not a reliable guide. Many of the larger denominations have

thin claims to orthodoxy, even by their own criteria. It is

clear to non-believers that what is now generally called orthodoxy

is really whichever line historically came out on top, often

by politicking, threats, deception, brute force, or the whim

of an emperor.

Any objective assessment would assign orthodoxy to denominations

that have been eliminated. The Nazarenes seem to have had the

strongest claims. Again, the Donatists were, if anything, ultra-orthodox

by the standards of the early Church. After them come the various

sects that were universally accepted as "orthodox"

except for beliefs or practices that, though now condemned,

are known to have been shared by early Christians. The sole

distinguishing feature of the Quartodecimans was that they continued

to calculate the date of Easter in the traditional way. The

heresy of the Montanists was that they continued to accept the

inspiration of the Holy Spirit after the "orthodox"

had changed their views about it. The Marcionites" principal

heresy was to regard God as a God of love rather than as a God

of fear. Other groups were regarded as heretical because they

paid salaries to their clergy — as late as AD 200 the orthodox

in Rome and elsewhere regarded this practice as outrageous.

The "heresy" of the Millenarians was to agree with

biblical views about the end of the world, while the Collyridians"

principal heresy was to worship the Virgin Mary as Queen of

Heaven long before other mainstream Christians accepted it as

orthodox to do so. The Antidicomarianites on the other hand

continued to hold traditional views about Mary after others

had abandoned them. They held, for example, that Mary had had

a normal marital relationship with Joseph after the birth of

Jesus.

The Roman Church developed its own ideas of heresy, often falling

into heresy itself by its own earlier standards. For example,

it had undoubtedly been heretical to attempt to enforce clerical

celibacy before popes tried to enforce it on their own priests.

In the Middle Ages the Spiritual Franciscans fell into heresy

according to the Roman Church by preaching absolute poverty,

copying the example of Jesus as closely as they could. Members

of many sects were persecuted as heretics for adhering to the

Ten Commandments. Because of the injunction "Thou shalt

not kill", some sects opposed capital punishment, and for

this belief they were often executed as heretics by the Christian

authorities*.

Of the surviving denominations, none has a clear claim to orthodoxy

that anyone else considers convincing. If we take as a criterion

the extent to which denominations have departed least from biblical

teachings (or that least contradict biblical teachings), then

we can discount all of the largest denominations, and must look

to sects out of the mainstream. There are a few tiny sects that

continue to honour the Sabbath rather than Sunday, practise

poverty as well as preach it, avoid man-made images of any living

thing, refuse to kill, and decline to swear oaths. If anyone

has a claim to orthodoxy it seems to be minority groups like

these.

The idea that there is a single straight trunk to the great

tree of Christianity is untenable. All present day denominations

represent branches, whether young or old, large or small. Generally,

it is not difficult to trace back today's offshoots through

the older branches from which they grew. To take a simple example,

Southern Baptists are an offshoot of the original Baptists,

who developed from the Anabaptists, a group of nonconformist

Protestant sects that had split off from the Roman Catholics.

The Roman Catholic Church itself may be seen as a branch of

the Orthodox Church, itself the successor of the Melkites, one

of the many outgrowths that vied with each other during the

Dark Ages, after the Pauline Christians had pruned back other

boughs of the Christian tangle-tree.

It has been remarked that the success or failure of the various

early Christian sects was determined not so much by comparative

reasonableness or skill in argument (for they practically never

converted each other), but by the differences in birth and death

rates in the respective populations. Whether or not this is

true, it is clear that what we call "orthodox" is

not objectively orthodox, it is "orthodox" only by

convention.

That famous fifth century definition of the one true Christian

faith as that which has been believed everywhere, always, and

by all would be convincing if there were such a faith, but there

is not, and apparently never has been. The definition was first

formulated by an orthodox Roman Catholic monk attacking the

novelties of St Augustine — novelties that have now become

the pinnacle of orthodoxy in the West. The simple truth is that

orthodox belief changes from place to place, from time to time,

and from denomination to denomination.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

|