| |

|

|

Christians have burnt each other,

quite persuaded

That the apostles would have done as they did

|

|

George Gordon, Lord Byron, Don

Juan

|

Introduction

Garroting

The Papal States

The Anglican Church

Abolition

Capital punishment was accepted as part of God's great design,

and no attempt was made to ban it by any right-thinking Christian.

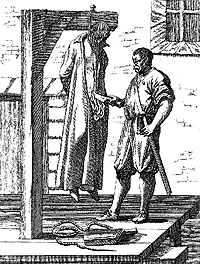

In the Middle Ages capital punishment was inflicted for religious

offences. Examples included robbing a church, sacrilege, eating

meat during Lent, cremating the dead, and omitting to be baptised*.

Petty vandalism against Church property also attracted the death

penalty. Churchmen advocated not only the death penalty but

also a range of accompanying horrors. Criminals were hanged

in chains. Sometimes bodies were gibbeted, i.e. they were coated

in tar to preserve them, then hung high up on a post, often

in sight of their family home, where the birds and the weather

would destroy them only after months or years. Some victims

were hanged, drawn, and quartered, after which their heart would

be held up to the crowd, and their severed head would be stuck

on a spike and left in some prominent place for everyone to

see. Here is a typical sentence :

You shall be drawn upon a hurdle through the open streets

to the place of execution, there to be hanged and cut down

while yet alive, and your body shall be opened, and your heart

and bowels plucked out, and your privy members cut off, and

thrown into the fire before your eyes; then your head to be

struck off, and your body divided into four quarters, to be

disposed of at the King's pleasure.... *

On God's behalf, English churchmen confirmed in the early nineteenth

century that it was perfectly acceptable to tear out the heart

and bowels of condemned but still living men. Some clergymen

advocated hanging whether the accused was guilty or not. One

argument was that capital punishment was a deterrent for the

criminally inclined, so the guilt or innocence of the individual

on trial was irrelevant*.

Another was that all sins are equally damnable in the eyes of

God, so the extreme penalty was appropriate for all*.

|

The heads of the Gunpowder Plotters,

hanged, drawn and quartered in 1606..

After quartering, the heads of those found guilty of treason

were stuck on spikes and dispayed in busy public places,

usually untill they rotted away and fell apart. Denying

criminals a Christian burial was a common element of punishments

for impious crimes under Christian laws.

|

|

|

Support for capital punishment provided a rare example of ecumenical

concord. As one modern cleric who made a study of the topic,

put it:

Orthodoxy, Reformed as well as Catholic, identified itself

closely with the secular power, supported the sword of the

secular arm, and benefited from it. God and the gallows together

kept society secure, anarchy at bay, and heresy suppressed*.

St

Thomas Aquinas had justified the death penalty, and the Roman

Church followed him. The death penalty was not merely permitted

by God: for certain crimes it was required by God.

Other authorities surpassed him in their zeal. Martin Luther

criticised the practice of the executioner asking forgiveness

of his victim, since the executioner, like the magistrate, was

an instrument of God*.

According to this view, the Christian officials responsible

for inflicting the death penalty had no more say in the matter

than the axe or rope or stake. The Church of England enshrined

its acceptance of the state's right to kill in Article 37 of

the 39 Articles of the Anglican Church. The full flourishing

of the code regarding capital punishment in western Europe coincided

with the Protestant ascendancy. The ultimate penalty was imposed

in England for such offences as destroying certain bridges,

impersonating a Chelsea pensioner, associating with gypsies,

stealing letters, and obstructing revenue officers. St

Thomas Aquinas had justified the death penalty, and the Roman

Church followed him. The death penalty was not merely permitted

by God: for certain crimes it was required by God.

Other authorities surpassed him in their zeal. Martin Luther

criticised the practice of the executioner asking forgiveness

of his victim, since the executioner, like the magistrate, was

an instrument of God*.

According to this view, the Christian officials responsible

for inflicting the death penalty had no more say in the matter

than the axe or rope or stake. The Church of England enshrined

its acceptance of the state's right to kill in Article 37 of

the 39 Articles of the Anglican Church. The full flourishing

of the code regarding capital punishment in western Europe coincided

with the Protestant ascendancy. The ultimate penalty was imposed

in England for such offences as destroying certain bridges,

impersonating a Chelsea pensioner, associating with gypsies,

stealing letters, and obstructing revenue officers.

In the American colonies, Christians passed capital laws based

on biblical injunctions.

|

from the The General Laws and Liberties

of the Massachusets Colony, 1641, Revised and Reprinted,

Cambridge, Massachusetts [Samuel Green, 1672, Law Library,

Rare Book Collection, US Library of Congress] - image

copy below

CAPITAL LAWES.

IF any man after legal conviction

shall HAVE OR WORSHIP any other God, but the LORD GOD:

he shall be put to death. Exod. 22. 20. Deut. 13. 6. &

10. Deut. 17. 2. 6.

2. If any man or woman be a WITCH,

that is, hath or consulteth with a familiar spirit, they

shall be put to death. Exod. 22. 18. Levit. 20. 27. Deut.

18. 10. 11.

3. If any person within this Jurisdiction

whether Christian or Pagan shall wittingly and willingly

presume to BLASPHEME the holy Name of God, Father, Son

or Holy-Ghost, with direct, expresse, presumptuous, or

high-handed blasphemy, either by wilfull or obstinate

denying the true God, or his Creation, or Government of

the world: or shall curse God in like manner, or reproach

the holy Religion of God as if it were but a politick

device to keep ignorant men in awe; or shal utter any

other kinde of Blasphemy of the like nature & degree

they shall be put to death. Levit. 24, 15. 16.

4. If any person shall commit any

wilfull MURTHER, which is Man slaughter, committed upon

premeditate malice, hatred, or crueltie not in a mans

necessary and just defence, nor by meer casualty against

his will, he shall be put to death. Exod. 21. 12. 13.

Numb. 35. 31.

5. If any person slayeth another

suddenly in his ANGER, or CRUELTY of passion, he shall

be put to death. Levit. 24. 17. Numb. 35. 20. 21.

6. If any person shall slay another

through guile, either by POYSONING, or other such develish

practice, he shall be put to death. Exod. 21. 14.

7. If any man or woman shall LYE

WITH ANY BEAST, or bruit creature, by carnall copulation;

they shall surely be put to death: and the beast shall

be slain, & buried, and not eaten. Lev. 20, 15. 16.

8. If any man LYETH WITH MAN-KINDE

as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed

abomination, they both shal surely be put to death: unles

the one partie were forced (or be under fourteen years

of age in which case he shall be seveerly punished) Levit.

20. 13.

9. If any person commit ADULTERIE

with a married, or espoused wife; the Adulterer &

Adulteresse shal surely be put to death. Lev. 20. 19.

& 18. 20. Deu. 22. 23. 27.

10. If any man STEALETH A MAN,

or Man-kinde, he shall surely be put to death. Exodus

21. 16.

11. If any man rise up by FALSE-WITNES

wittingly, and of purpose to take away any mans life:

he shal be put to death. Deut. 19. 16. 18. 16.

12. If any man shall CONSPIRE,

and attempt any Invasion, Insurrection, or publick Rebellion

against our Common-Wealth: or shall indeavour to surprize

any Town, or Townes, Fort, or Forts therin; or shall treacherously,

& persidiously attempt the Alteration and Subversion

of our frame of Politie, or Government fundamentally he

shall be put to death. Numb. 16. 2 Sam. 3. 2 Sam. 18.

2 Sam. 20.

13. If any child, or children,

above sixteen years old, and of sufficient understanding,

shall CURSE, or SMITE their natural FATHER, or MOTHER;

he or they shall be put to death: unles it can be sufficiently

testified that the Parents have been very unchristianly

negligent in the eduction of such children; or so provoked

them by extream, and cruel correction; that they have

been forced therunto to preserve themselves from death

or maiming. Exod. 21. 17. Lev. 20. 9. Exod. 21. 15.

14. If a man have a stubborn or

REBELLIOUS SON, of sufficient years & uderstanding

(viz) sixteen years of age, which will not obey the voice

of his Father, or the voice of his Mother, and that when

they have chastened him will not harken unto them: then

shal his Father & Mother being his natural parets,

lay hold on him, & bring him to the Magistrates assembled

in Court & testifie unto them that their Son is stubborn

& rebellious & will not obey their voice and chastisement,

but lives in sundry notorious crimes, such a son shal

be put to death. Deut. 21. 20. 21.

15. If any man shal RAVISH any

maid or single woman, comitting carnal copulation with

her by force, against her own will; that is above the

age of ten years he shal be punished either with death,

or with some other greivous punishmet according to circumstances

as the Judges, or General court shal determin.

|

The details are interesting - for example Articles 13 and 14

both allow the execution of children, but 13 applies to daughters

while 14 does not. The Christians who framed these laws clearly

had no concept of the Old Testament having been abregated by

the New, but they did add mitigating factors (as in 14). Note

that 15 has no biblical reference, presumably because the biblical

penalty was a small fine, and considered wholly inadequate by

17th century Christians.

The Roman Church carried out countless thousands of executions

and continued to sanction its own secret executions well into

the nineteenth century. Other denominations also approved of

capital punishment. Methodist ministers took children to watch

public executions, such scenes being considered "improving".

Wesley himself had been keen on gibbeting and had wanted to

extend the practice to suicides. Calvinists concurred. A leading

nineteenth century minister styled the "Champion of the

Sacred Cause of Hanging", was critical of the exercise

of mercy in capital cases. As he pointed out, God himself had

tried mercy with Cain, and everyone knew how badly that had

turned out.*

|

"Execution of Breaking on the Rack",

illustration by William Blake in John Gabriel Stedman's

The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted

Negroes of Surinam (1796). John Gabriel Stedman relates

that: "The third negro, whose name was Neptune, was

no slave, but his own master, and a carpenter by trade;

he was young and handsome, but having killed the overseer

of the estate Altona, in the Para Creek, in consequence

of some dispute, he justly forfeited his life.... he was

sentenced to be broken alive upon the rack, without the

benefit of the coup de grace or mercy-stroke. Informed

of the dreadful sentence, he composedly laid himself down

on his back on a strong cross, on which, with arms and

legs expanded, he was fastened by ropes: the executioner,

also a black man, having now with a hatchet chopped off

his left hand, next took up a heavy iron bar, with which,

by repeated blows, he broke his bones to shivers, till

the marrow, blood, and splinters flew about the field;

but the prisoner never uttered a groan nor a sigh. ...

He then begged that his head might be chopped off; but

to no purpose. At last, seeing no end to his misery, he

declared, “that though he had deserved death, he

had “not expected to die so many deaths: however,

(said he) you christians have missed your aim at last

..." He lived on for some three hours.

|

|

|

Garrotting

The garrote was the preferred device used for capital punishment

in Catholic Spain for hundreds of years. Originally the convict

would be beaten to death with a club (a garrote in Spanish).

This later developed into a method of strangulation. The victim

was tied to a wooden stake, with a loop of rope placed around

his neck. A stick was placed in the loop and twisted by an executioner,

causing the rope to tighten until it strangled the victim to

death. In time the method was refined so that the victim sat

on a stool attached to a stake, to which the victim was bound,

and the executioner tightened a metal band around the victim's

neck with a crank.

|

The design of a basic garrote

|

Detail of Le garrot, by Velasquez,

c 1810

Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille.

|

|

|

|

Around 1810 the earliest known metal garrote appeared in Spain.

In 1828, this garrote was declared the sole method for executing

civilians.

|

Garrot vil, by Ramón Casas, painted

in 1894, Museu Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Garrotting was generally carried out in public, and attended

by Christian ceremony.

Note the number of Catholic officials in black costumes

within the cordon at this garrotting in Barcelona

|

|

|

In May 1897, the last public garroting in Spain was performed

in Barcelona. After that, all executions were performed inside

prisons.

|

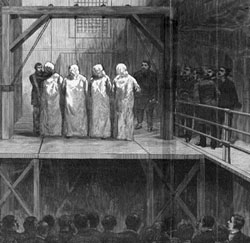

A mass garrotting.

Christian priests were an integral part of the ceremony

surrounding capital punishment, including garrotting.

|

|

|

|

|

At the prompting of the Catholic Church, the right-wing Spanish

legislature enacted laws against Freemasons. Under these laws,

80 Freemasons were garroted to death in Málaga, and many

more in other towns. With the help of Catholic priests like

Father Jean Tusquets and Franco's own chaplain, some 80,000

men were executed as Freemasons, (even though there had probably

been around 5,000 Freemasons in Spain at the time).

|

Priests were always available to validate

the proceedings in the name of God

|

|

|

Two men were garrotted in Spain in 1974, a year before the

death of Franco. The garrote was abolished in 1978, soon after

the Catholic Church lost its influence over Spanish government.

|

Le Progres Illustre, 21 February, 1802,

reporting the execution of anarchists at Xeres

|

|

|

Where the USA took over Spanish colonies, they kept the Spanish

of capital punishment, at least for a while. American military

authorities in Puerto Rico used the garrote to execute at least

five convicted murderers in 1900. American authorities also

kept the garrote in the Philippines after the colony was captured

in 1898. The garrote was abolished in 1902 (Act No. 451, passed

September 2, 1902).

A version of the garrote incorporated a metal spike fixed into

the stake and directed at the skull or spinal cord. The spiked

version, called the Catalan garrote, was used as late as 1940.

|

An execution by garrotting in 1901

|

|

|

|

|

This Catalan Garrote is designed

not only garrote the victim, but also drive a spike

into the back of the victim's head as the garrote

is tightened

|

|

|

|

The Papal States

Since God not only approved capital punishment, but required

Christian rulers to apply it to their subjects. It followed

that as sovereign of the Papal States, the Pope was required

to execute wrongdoers. A succession of hundreds of popes therefore

evolved methods of capital punishment, none of them noticeably

more humane than those of other Christian monarchs.

In extreme cases, those condemned would be hanged, drawn and

quartered. For others popes developed a particularly gruesome

method of method of public execution. Churchmen were reluctant

to shed blood, which explains why monks were forbidden to carry

out surgery, why bishops used maces when fighting in medieval

wars, why witches and heretics were burned alive, and perhaps

why popes favoured the Mazzatello as a method of execution.

A Mazzatello is a large, long-handled mallet, used to smash

in the victim's skull. The victim would be led to a scaffold

in a public square of Rome, accompanied by a priest. already

installed on the scaffold was a coffin and a masked executioner,

dressed in black. The executioner would swing the mallet to

gain momentum, and bring it down on the head of the victim.

The fist blow was rarely fatal. (A variation of this method

appears in Alexandre Dumas' novel, The Count of Monte Cristo,

as la mazzolata, when a prisoner sentenced to execution is bludgeoned

on the side of his head with a mace.)

The papal Mazzatello does not survive,

but would have looked something like this.

This mazzatello was used by Catholic Ustaška guards

to crush the skulls of non-Catholic prisoners (including

Serbs, Jews and Roma) at Jasenovac in Croatia, accounting

for some of the tens of thousands killed there between

1941 and 1945.

|

|

|

According to one author, the mazzatello constituted "one

of the most brutal methods of execution ever devised, requiring

minimal skill on the part of the executioner"*.

Another cites mazzatello as an example of an execution method

devised by the Papal States that "competed with and in

some instances surpassed those of other regimes for cruelty".*

The mazzatello was used within the Papal States from the late

18th century up until 1870, when the French army seized the

papal states and stopped the practice of hammering people to

death in public.

Throughout most of Christian history bishops exercised temporal

as well as spiritual authority. One corrolory of this was that

they acted as secular as well as spiritual judges. In line with

Church teachings they routinely imposed the death sentence.

As secular judges they routinely imposed sentences of torture

and death. As spiritual judges they were not permitted to spill

blood, so they handed over heretics, blasphemers and other religious

disenters to the secular autyhorities for execution. These secular

authorities (sometimes themselves wering a secular had) were

responsible for executing sentence.

There are countless examples of prince-bishops exercising this

dual power, but the best example is probably the Bishop of Rome,

soveriegn ruler of the Papal States (now reduced to the Vatican

state). The Bishops of Rome perfectly illustrate Catholic teaching

and practice with respect to capital punishment.

Capital punishment was not only permitted, it was required

by Church teaching. It was also popular. It was claimed that

in 1585, under Pope Sixtus V there were more severed heads on

the Castel Sant'Angelo bridge than melons in the markets.

Methods

The traditional method of execution before 1816, were beheading

and hanging. In special cases convicts were bludgeoned to death

with a huge mallet, then had their throats cut.. The executioner

would swing his mazzatello through the air and bring

it crashing down on the prisoner's head. This replicated how

cattle were killed: a blow on the head followed by having the

throat cut. Whatever the means of death, the body might then

be quartered for public display.

Beheading was the standeard penalty for less serious crimes

such as larceny, robbery, and assault. though it was on occasion

applied for treason (Prospero Ciolli, 22 September 1832) and

for lèse majesté (Leonida Montanari and Angiolo

Targhini, 23 November 1825), and for stealing church property.

On 21 July, 1840, Luigi Scopigno from Rieti was beheaded at

the Ponte Sant'Angelo, for the sacrilegious theft of a container

containing sacred hosts.

Hanging was also a penalty for theft and robbery, and also

for causing criminal damage and for forgery. Tommaso Rotiliesi,

was hanged at the Ponte Sant'Angelo, on 9 June, 1806 for slightly

wounding a French officer. Hanging and Quartering seems to have

been the standard punishment for murder, though it could also

be applied for robbery.

Bludgeoning seems to have been reserved for particularly brutal

murders, including patricide, murdering churchmen, and multiple

murders. Convicts who were bludgeoned, and had their throats

cut, were frequently quartered as well.

Sometimes it is not clear what means were employed. 22 year

old Giovani Battista Rossi convicted of larceny, was sentenced

to an exemplary death on 3 August 1844. In 1855 at least eight

men were senteced to the "ultimate torment". On 23

March, 1822, Francesco, son of Niccola Ferri, was executed by

shooting. In other cases, additional features might be added

to standard punishments. For the crime of stealing two cibori,

Giovani Batta Genovesi was hanged and quartered on 27 February,

1800, then had his corpse burnt at the Ponte Sant'Angelo. His

head was then taken to the Arch of the Holy Spirit. Similar

punishments were applied to men who killed a priest in the same

year.

These punishments were imposed by the Pope in his role as temporal

sovereign. There was another set of crimes that were religious

in nature. A few notable examples are:

- Arnold of Brescia (c. 1090 – June 1155), was an Italian

canon regular from Lombardy. He called on the Church to renounce

property ownership. Arnold was hanged by the papacy, then

was burned posthumously by papal guards and his ashes thrown

into the River Tiber.

- Gerard Segarelli, founder of the Apostolic Brethren (July

18, 1300). In 1300 he was interrogated by the Grand Inquisitor

of Parma. He was found guilty of relapsing into errors formerly

abjured, and burnt at the stake.

- Fra Dolcino, Italian preacher of the Dulcinian movement,

burnt at the stake in 1307 for heresy.

- Matteuccia de Francesco (died 1428) was an Italian nun,

and alleged witch, known as the "Witch of Ripabianca"

after the village where she lived. She was put on trial in

Rome in 1428, accused of being a prostitute, having committed

desecration with other women and of the selling of love potions

since 1426. She confessed to having sold medicine and of having

flown to a tree in the shape of a fly on the back of a demon,

having smeared herself with an ointment made of the blood

of newborn children. She was judged guilty of sorcery and

sentenced to be burned at the stake.

- Matteuccia de Francesco, Italian nun and alleged "Witch

of Ripabianca" (1428)

- Girolamo Savonarola (along with Fra Domenico da Pescia and

Fra Silvestro), Dominican priest and leader of Florence (May

23, 1498)

- Cardinal Carlo Carafa and Giovanni Carafa, Duke of Paliano,

nephews of Paul IV, sentenced to strangulation in prison and

beheading, respectively, by Pius IV, as his first public act

(March 5, 1561)

- Pomponio Algerio, civil law student at the University of

Padua (1566)

- Pietro Carnesecchi, Italian humanist (October 1, 1567)

- Aonio Paleario, Italian Protestant (July 3, 1570)

- Menocchio, Friulian miller, mayor, and philosopher (1599)

- Giordano Bruno, Italian priest, philosopher, cosmologist,

(February 17, 1600)

- Ferrante Pallavicino, Italian satirist (March 5, 1644)

The Church's Role

The Church was prominent throughout and coordinated all aspects

of what was a quasi sacred act, rather like an auto da fe.

As one modern Catholic commentator says "it was a sacred

act, rich with ritual and theological meaning hallowed by centuries

of tradition. It was, in fact, a liturgy." *

The ritual began with the announcement of an execution. Official

notices were posted on church doors. On the morning of the execution,

the pope said a prayer for the condemned. A priest would visit

the Pope's executioner to hear his confession and celebrate

Mass. The execution was solemnized by a religious Order, the

monks of the Arciconfraternita della Misericordia, or

Brotherhood of Mercy. These monks celebrated various rituals

surrounding the execution and burial. The monks stayed with

the condemned in their last 12 hours. Members of the brotherhood

wrote prayer books and catechisms for the condemned, emphasising

the requirements for a mors bon Christiana -- "a

good Christian death." The monks led the condemned in a

sacred procession. Altar boys went first, ringing bells. Monks

followed chanting litanies in a cloud of incense, carrying a

crucifix. The monks would hold the crucifix toward the condemned,

so that it would be the last thing he saw.

This "gallows pietism." can be seen as a form of

expiation, or atonement. The scaffold was an occasion of grace,

almost sacramental. Devotional literature compared the redemptive

value of the blood spilled to Christ's sacrifice on the cross.

Execution took place as papal palaces: the Castel Sant'Angelo

bridge, the Piazza del Popolo, and Via dei Cerchi near the Piazza

della Bocca della Verità. Papal dragoons provides security.

To celebrate executions the Church put on public festivals.

Crowds would lay bets on all aspects of the procedings. As for

Christian public executions everywhere, whole families came

to enjoy the spectacle. As the blade descended, fathers slapped

their children's heads when the blade came down, causing the

same frisson they remembered when their their own fathers had

slapped theirs.

The End of Capital Punishment by the Pope

In 1764 Cesare Beccaria, anti-death penalty tract "On

Crimes and Punishments" was published, changing secular

attidutes to capital punishment. In 1786 the Grand Duchy of

Tuscany became the first sovereign state to ban the death penalty.

The Catholic Church remained aloof from this development, adhering

to its traditional line.

The pope lost political control of Rome to Napoleon in 1798

and did not get it back until the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

From 1816 on the guillotine was used scores of times by papal

warrant. The guillotine remained busy up to the end of the pope-king's

rule. Its final use came on July 9, 1870, shortly before Italian

revolutionaries captured Rome. Agatino Bellomo, became the last

person executed by the Papal States, two months before Rome

was captured by Italian army and the papal states ceased to

exist. Capital punishment in Vatican City was legal from 1929

to 1969, though no known executions took place.

The Anglican Church

The Anglican Church had supported capital punishment since

its foundation, continuing its historical inheritance from the

Catholic and ultimately the Orthodox Church. No Anglican movement

for abolition was so much as considered for many centuries.

Christian Evangelicals like the nineteenth century politician

Anthony Ashley-Cooper (later seventh Earl of Shaftesbury) advocated

the traditional view that God not only permitted capital punishment

but also demanded it*.

Judges pointed out to those found guilty of certain crimes that

God required them to die.

Churchmen claimed that the deterrent effect of capital punishment

was enhanced by due solemnity, mystery and awe. The Church therefore

buttressed the ceremony of execution, and surrounded it by ritual.

In England a chaplain was on hand in court to intone Amen

to the judge's sentence of death. A prison chaplain might hold

a service before the execution with a coffin displayed in the

presence of the congregation and the condemned prisoner. After

English executions were confined to prisons in 1868, a black

flag was hoisted over the prison on execution days; a bell would

toll; and the chaplain would intone the burial service as he

accompanied the condemned prisoner to the gallows*.

The Church was involved throughout, into the twentieth century,

validating the procedure on behalf of God. It was generally

accepted that the main business of prison clergymen was to break

the spirits of capital convicts so that they would offer no

physical resistance to the hangman*.

Sometimes the chaplain himself gave the signal to carry out

the execution.

Time and time again bishops and archbishops opposed the abolition

of capital punishment. In 1810 the Archbishop of Canterbury

and six other bishops helped defeat a bill that would have abolished

the death penalty for stealing five shillings from a shop. Capital

punishment was so much part and parcel of the Christian faith

that bishops would go to almost any lengths to keep it. When

secularists advocated the abolition of the death penalty, the

bishops rushed to its support. When it looked like public revulsion

at public executions might force Parliament to abolish capital

punishment in the mid-nineteenth century, zealous Christians

pressed for hanging to be carried out inside prisons. The idea

was that, once removed from the public gaze, executions could

continue without fuss or popular revulsion. This plan was advocated

for example by Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford*.

So it was that in 1868 public executions ceased in England and

private ones began. As the bishop had hoped, pressure for abolition

subsided.

Well into the twentieth century most English bishops were in

favour of capital punishment and used their votes in the House

of Lords to oppose abolition. For example the bench of bishops

helped defeat the Criminal Justice Bill of 1948 during its passage

through the House of Lords. In the 1950s it looked again as

though Parliament might abolish the death penalty. The Archbishop

of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, was alarmed that this attempt

might succeed. He therefore adopted a similar technique to that

adopted by Bishop "Soapy Sam" Wilberforce

in the previous century. This time public sentiment was opposed

to the death penalty, even behind closed prison doors. In order

to retain capital punishment the Archbishop advocated classifying

degrees of murder. In this way he hoped to retain the death

penalty for at least some crimes. The Christian line was that

it was better to hang some offenders rather than none at all.

Fisher was not keen to have his traditionalist views opposed:

"Anyone who says that it is unchristian to hang puts himself

out of court" he wrote*

Other Churches held similar views. When abolition of the death

penalty was again being considered in Britain in the 1960s,

Cardinal Godfrey appeared on television to advocate the traditional

Roman Catholic line. As he said, the state had not merely the

right, but the duty to exact the death penalty

whenever, in its own judgement, the life of the community was

threatened by a particular sort of crime*.

The

first stirrings of opposition to the death penalty in Britain,

in the early nineteenth century, came principally from those

who rejected the prevailing Christian consensus. The philosopher

Jeremy Bentham, reputedly an atheist, and the poet Shelley,

an avowed atheist, both opposed capital punishment, supported

by Quakers*. They were

opposed by all right-thinking organised Churches*.

As we have seen, in the House of Lords the bishops consistently

supported capital punishment. The loudest parliamentary voices

raised in the Lords against the death penalty in the nineteenth

century belonged to men like the godless Lord Byron, as outside

the Lords they belonged to atheists like Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891),

Annie Besant (1847-1933) and George Holyoake (1817-1906). Holyoake

wondered why the Archbishop of York could find time to condemn

sensationalist novels but not to utter a word against public

execution*. The

first stirrings of opposition to the death penalty in Britain,

in the early nineteenth century, came principally from those

who rejected the prevailing Christian consensus. The philosopher

Jeremy Bentham, reputedly an atheist, and the poet Shelley,

an avowed atheist, both opposed capital punishment, supported

by Quakers*. They were

opposed by all right-thinking organised Churches*.

As we have seen, in the House of Lords the bishops consistently

supported capital punishment. The loudest parliamentary voices

raised in the Lords against the death penalty in the nineteenth

century belonged to men like the godless Lord Byron, as outside

the Lords they belonged to atheists like Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891),

Annie Besant (1847-1933) and George Holyoake (1817-1906). Holyoake

wondered why the Archbishop of York could find time to condemn

sensationalist novels but not to utter a word against public

execution*.

|

Execution of Doctor Crippen, in Le Petit

Journal illustré, 4th December 1910.

From the French Revolution onwards the French considered

hanging barbaric and made much of the attendent religious

ceremony and the role of the anglican priest in Britain.

|

|

|

The Churches could have demolished the moral case for capital

punishment, but instead they bolstered it:

In a Christian country, such as England was, a death penalty

devoid of religious sanction could not have survived. It was

an issue over which the church could have exercised a moral

hegemony and failed to do so. It shadowed public opinion rather

than led it. It left the moral high ground to Quakers, lapsed

Jews, maverick Christians of all denominations, and men and

women of none*.

In the second half of the twentieth century the bishops finally

adopted the secularist view. Prison chaplains in Britain got

round to considering the morality of the death penalty just

as Parliament abolished it in 1969.

|

Le Petit Journal illustré (21

janvier 1923) - Une femme expie son crime

"A woman expiates her crime". As usual, right

up to abolition of hanging, Anglican clergymen played

a prominant role in the macabre ceremonial that attended

British executions.

|

|

|

The same pattern was followed in North America. Quaker laws

proposed for Pennsylvania had been vetoed by London in the seventeenth

century as they were far more lenient than the capital laws

of the mother country*.

The complete abolition of the death penalty was first proposed

in a paper read at the house of Benjamin Franklin. This paper

likened public execution to "a human sacrifice in religion"*.

In the years to come the battle was largely between on the one

hand freethinkers, and on the other Calvinists and other traditional

Churches. In Continental Europe the abolitionist cause was espoused

by independent writers like Goethe and Victor Hugo but opposed

by the Churches. As in Britain and America all abolitionists

were condemned as infidels.

|

Last public execution in the USA. Rainey

Bethea was be publicly executed

on 14 August, 1936 in Owensboro, Kentucky.

Mistakes in performing the hanging and the attendant media

circus contributed to

public pressure for end of public executions in the United

States.

|

|

|

|

|

Abolition

The only Christian sect consistently to have opposed the death

penalty was the Quakers. Like non-Christians who led the reform

movement, they regarded it as immoral. This is all rather an

embarrassment now in liberal countries. Liberal churchmen would

have preferred it if the Church had opposed the death penalty.

In fact most Anglicans and Protestants have opposed the death

penalty since the 1960s, and in 1999 they were joined for the

first time by the Pope. Attachment to capital punishment is

now unfashionable, so most Churches around the developed world

tend to play down their traditional views. Many clergymen do

their best to make out that their Church has always supported

the biblical injunction Thou shalt not kill, a principle

that in truth was adopted only after Western society had been

thoroughly secularised. Only in places like the Bible belt in

the USA do traditional Christian views still predominate. Capital

punishment continues to be inflicted in such places, despite

secular opposition.

More social issues:

|

from the The General Laws and Liberties

of the Massachusetts Colony, 1641, Revised and Reprinted,

Cambridge, Massachusetts

[Samuel Green, 1672, Law Library, Rare Book Collection,

US Library of Congress]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

| |

| |

| More Books |

|

|

|